What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

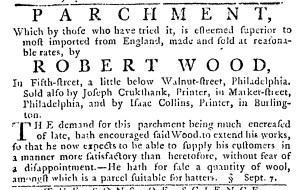

“PARCHMENT … Made and sold … [in] Philadelphia.”

In the early 1770s, Robert Wood made and sold parchment in Philadelphia, yet he did not confine his marketing or distribution of his product to that city and its hinterland. As spring approached in 1775, he ran an advertisement in the supplement that accompanied the March 2 edition of the New-York Journal, advising prospective customers that they could acquire his parchment from local agents. John Holt, the printer of the New-York Journal, and Hugh Gaine, the printer of the New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, each stocked Wood’s parchment along with books, stationery, and writing supplies at their printing offices. In addition, Joseph Dunkley, a painter and glazier, also supplied Wood’s parchment at his workshop “opposite the Methodist Meeting House.” The New-York Journal circulated beyond the city, so some prospective customers would have found it more convenient to acquire Wood’s parchment from Isaac Collins, a printer in Burlington, New Jersey. According to previous advertisements, Collins had been peddling Wood’s parchment to “friends to American Manufactures” for several years.

Wood asserted that the “Demand for this Parchment [was] much increased of late,” though he left it to readers to imagine why that was the case. Most would assume that the Continental Association, a nonimportation agreement that went into effect on December 1, 1774, played a role in increased demand for parchment produced in the colonies. Wood likely intended for prospective customers to draw the conclusion that the quality of his product, not merely its availability, contributed to the demand. He declared that “those who have tried it … esteemed [it] superior to most imported from England.” He was bold enough to resort to superlatives, claiming that customers considered his parchment better than any imported to the colonies, yet he offered firm assurances about it quality. Wood had recently met with so much demand for his parchment that he “extend[ed] his Works … to be able to supply his Customers in a manner more satisfactory than heretofore, without Fear of a Disappointment.” In other words, he stepped up production to expand his inventory so every customer who wished to purchase his parchment could do so. Wood answered the call of the eighth article of the Continental Association with his own “Industry” in producing “Manufactures of this Country” as alternatives to imported goods.