What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“A patern card of the above holes may be seen at his house.”

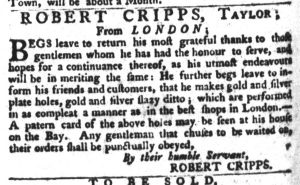

Robert Cripps, a tailor originally from London, used his advertisement in the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal to draw attention to another form of marketing intended to entice potential clients to avail themselves of his services. After announcing that he “makes gold and silver plate holes, gold and silver slazy [holes],” he informed readers that “A patern card of the above holes may be seen at his house on the Bay.” Print culture accounted for much of the marketing in eighteenth-century America as advertisers distributed trade cards, billheads, and catalogs and inserted notices in newspapers and on magazine wrappers, but print was not the only – or even always the best – way to generate interest and incite demand. Material culture offered an attractive and viable alternative.

No matter how articulate or elaborate Cripps and other tailors could have been in describing their work in advertisements, doing so certainly could not have compared to allowing potential customers to examine finished work for themselves. Pattern cards provided a means of making this possible that had several advantages. Tailors and customers did not have to handle finished garments made for other clients, nor did tailors need to keep extensive inventory on hand. Instead, pattern cards allowed them to demonstrate an array of possibilities. Pattern cards presented consumers with an array of choices similar to the “assortment of goods” that commonly appeared in lengthy list-style advertisements placed by shopkeepers. In selecting the style of buttonholes that fit their taste and budget, clients asserted control over interactions with those they hired as well as, ultimately, their appearance rather than settling for whatever wares tailors might have otherwise foisted on them. Cripps could construct garments that were distinctive and special, but he did so at the direction of his clients who made a variety of choices about their apparel, including the type of buttonholes they selected from the pattern card. The pattern card was a useful tool, not only because it presented samples but perhaps more importantly because it excited potential clients’ imaginations and stoked their desire and demand for Cripps’ tailoring services.

**********

While the “plate holes” in this advertisement were familiar to eighteenth-century consumers, they are no longer part of the lexicon of most modern consumers when they purchase clothing. I turned to specialists in the histories of textiles and fashion for assistance in determining what Cripps meant. Kimberly Alexander, Gina Barrett, and the pseudonymous Scrapiana graciously and insightfully pointed me in the right direction via a conversation on Twitter last week. Barrett drew my attention to both of the garments pictured here.

“Plate holes” referred to buttonholes created by stitching over flat metal plates on either side of the hole. See, for example, a British waistcoat from the 1740s now in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum. For an even more elaborate example, see the circa 1760 French waistcoat at the Kent State University Museum. In contrast, “slazy” holes did not have metal plates.