What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Annapolis Constitutional Post-Office.”

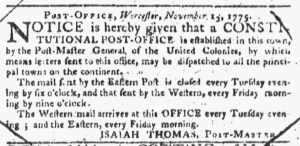

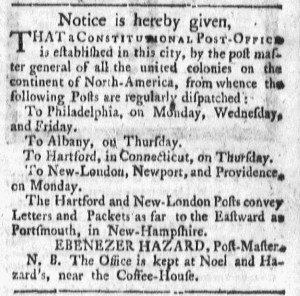

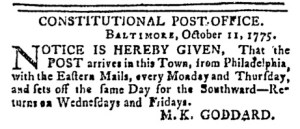

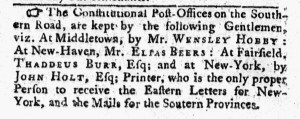

In early December 1775, William Whetcroft became the latest postmaster to run a newspaper advertisement promoting a local branch of the Constitutional Post Office established by the Second Continental Congress. In October, Mary Katharine Goddard placed a notice about the Baltimore office in the Maryland Journal. Otherwise, advertisements for local branches appeared in newspapers published in New England, New York, and Pennsylvania, but not yet in newspapers from colonies south of Maryland. The headline for this newest advertisement proclaimed, “Annapolis Constitutional Post-Office,” alerting readers of the Maryland Gazette that they had an alternative to the British imperial system. Whetcroft commenced with an overview of his office’s schedule: “the Northward and Southward mail arrive at this office every Friday at two o’clock, and return the same day at six.” In addition, “on Monday a rider leaves this town for Baltimore, and returns on Tuesday with the Northward mail.”

Yet Whetcroft used his advertisement to relay more than just the logistical details. He gave an overview of the purpose that the Constitutional Post Office served as the imperial crisis intensified, hostilities commenced, and some colonizers considered whether they should declare independence rather than continue seeking redress of their grievances against Parliament. “The constitutional office having been instituted by the congress,” the postmaster explained, “for the security and ready conveyance of letters, and all kinds of intelligence through this continent; and as the same has been attended with a great expence, it is not doubted that all well-wishers to the present laudable opposition in America, will promote the same, by sending and procuring to be sent all letters, packages, &c. to the constitutional post-office.” Supporters of the American cause had a civic duty, Whetcroft asserted, to make use of this service.

Frederick Green, the printer of the Maryland Gazette, gave Whetcroft’s notice a privileged place the first time it appeared in that newspaper. It appeared as the second advertisement following the news, preceded only by Green’s own advertisement for the almanac he just published and sold at the printing office. As much as Green may have been a supporter of the Constitutional Post Office, he still had to earn his livelihood with his own endeavors! Still, the printer had room for only two advertisements at the bottom of the final column on the second page. He could have chosen from among several of a similar length to Whetcroft’s advertisement, yet he selected the notice about the Constitutional Post Office to appear alongside news of the revolutionary events taking place in Maryland and beyond. In subsequent editions, that advertisement ran intermingled among others, but that was common practice for notices that printers initially gave privileged places the first time they ran in their newspapers.