What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“Supplement to the South-Carolina Gazette, and Country Journal.”

Charles Crouch, printer of the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal, had far more content than would fit in a standard issue on June 23, 1772. Like other newspapers printed throughout the colonies, his weekly newspapers consisted of four pages created by printing two pages on each side of a broadsheet and then folding it in half. On that particular day, Crouch devoted two pages to news and two pages to advertising. That left out a significant number of advertisements of all sorts, including legal notices, catalogs of goods sold by merchants and shopkeepers, and notices that described enslaved people who liberated themselves and offered rewards for their capture and return. Since advertising represented significant revenue for printers, Crouch did not want to delay publishing those advertisements, especially since his newspaper competed with both the South-Carolina Gazette and the South-Carolina and American General Gazette to attract advertisers.

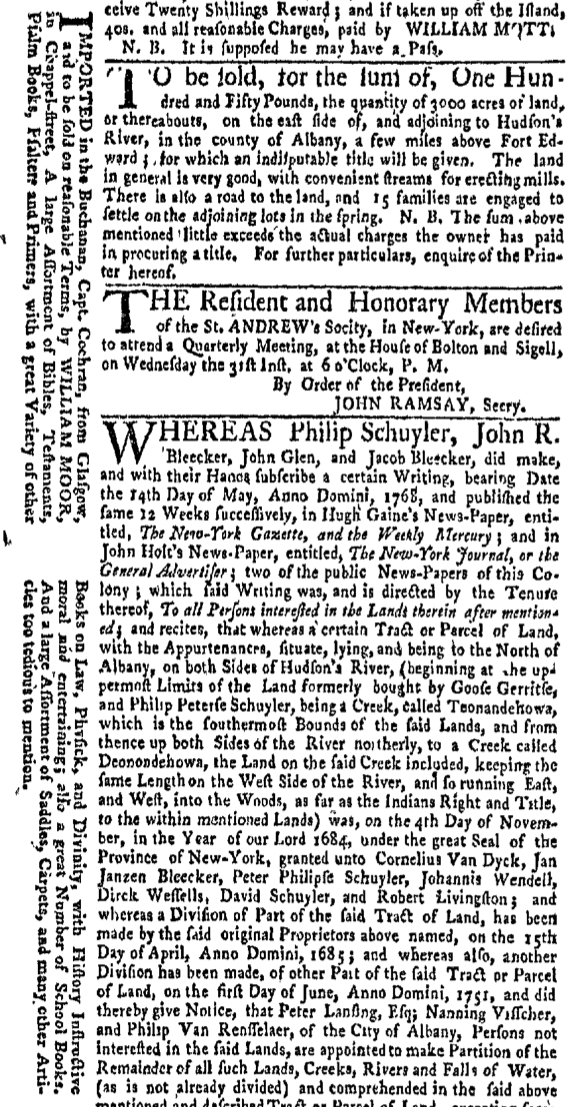

To solve the problem, Crouch printed and distributed a supplement comprised entirely of advertising. From New England to South Carolina, printers often resorted to supplements when they found themselves in Crouch’s position. Even as he devised the supplement to accompany the June 23 edition, Crouch carefully considered his resources and the amount of the content he needed to publish. He selected a smaller sheet than the standard issue, one that allowed for only two columns instead of three. That could have resulted in wide margins, but Crouch instead decided to print shorter advertisements in the margins, rotating type that had already been set to run perpendicular to the two main columns. That created room for four additional advertisements per page, a total of sixteen over the four pages of the entire supplement. With a bit of ingenuity, Crouch used type already set for previous issues or that could easily integrate into subsequent issues rather than (re)setting type just to accommodate the size of the sheet for the June 23 supplement. Crouch managed to meet his obligation to advertisers who would have been displeased had he excluded their notices while simultaneously conserving and maximizing the resources available in his printing office.