What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“All those that really have the Welfare of their Country at Heart, are desired to consider seriously, the Importance of a Paper Manufactory to this Government.”

The Townshend Act assessed new taxes on all sorts of imported paper. When it went into effect on November 20, 1767, many colonists vowed to encourage and purchase domestic manufactures, especially paper, as a means of resisting Parliament overreaching its authority. Calls for colonists to collect linen rags and turn them over to local papermakers, not uncommon before the Townshend Act, took on a new tone once the legislation went into effect.

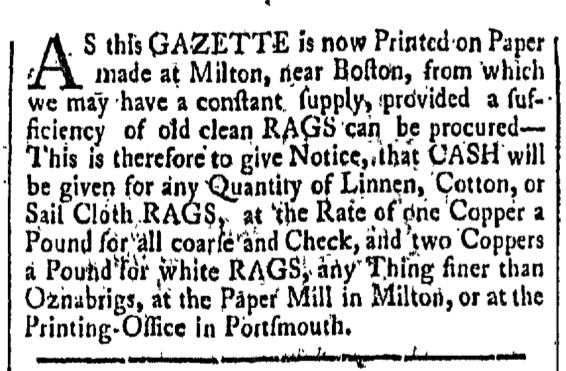

The “Manufacturers of PAPER at Milton” in Massachusetts placed an advertisement in the Boston-Gazette in late November 1767. In it, they addressed “All Persons dispos’d in this Wat to encourage so useful a Manufacture.” The “Manufacturers” aimed to collect enough rags quickly enough to replenish the “large Quantities of Paper” that “fortunately arriv’d from Europe before the Duties could be demanded.” Ultimately, the “Manufacturers” wished to produce so much paper that colonists would never have to purchase imported paper again (and thus avoid paying the new taxes), but that required the cooperation of consumers participating in the production process by saving their rags for that purpose.

In January 1768, Christopher Leffingwell placed a similar advertisement in the New-London Gazette. He issued a call for “CLEAN LINEN RAGS” to residents of Connecticut, calling collection of the castoffs “an entire Saving to the COUNTRY.” He encouraged “every Friend and Lover” of America to do their part, no matter how small. Leffingwell suggested that producing paper locally benefited the entire colony; the economy benefited by keeping funds within the colony rather than remitting them across the ocean as new taxes. With the assistance of colonists who collected rags, Leffingwell could “supply them with as good Paper as is imported from Abroad, and as cheap.”

John Keating joined this chorus in February 1768. In an advertisement in the New-York Journal he even more explicitly linked the production and consumption of paper to the current political situation than Leffingwell or the “Manufacturers of PAPER at Milton.” He opened his notice by proclaiming, “All those that really have the Welfare of their Country at Heart, are desired to consider seriously, the Importance of a Paper Manufactory to this Government.” Purchasing paper made in America represented a double savings: first on the cost of imported paper and then by avoiding “a most arbitrary and oppressive Duty” that “further drain’d” the colony of funds that would never return.

Keating acknowledged that collecting rags might seem small and inconsequential, yet he assured colonists that collectively their efforts would yield significant results. He recommended that they cultivate a habit of setting aside their rags by hanging a small scrap in a visible place “in every House” as a reminder. Readers who followed that advice transformed domestic spaces into political venues; otherwise mundane actions took on political meaning as both members of the household and visitors noticed clean linen rags hung as reminders to encourage domestic production and consumption. In the end, Keating predicted that this “would have the desired Effect, and supply us with Paper at home sufficient for our own Use … whereas now we are obliged to send Money abroad, not only to pay for Paper at a high Price, but an oppressive Duty upon it into the Bargain.” Keating not only advanced a “Buy American” campaign but also encouraged colonists to participate in the production of domestic manufacturers for the common good.