What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Uneasiness arising in the minds of people from the conduct of myself and family upon the fast day.”

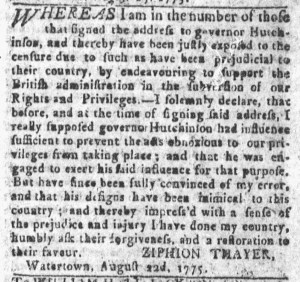

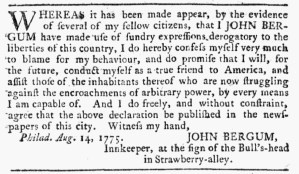

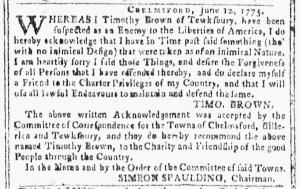

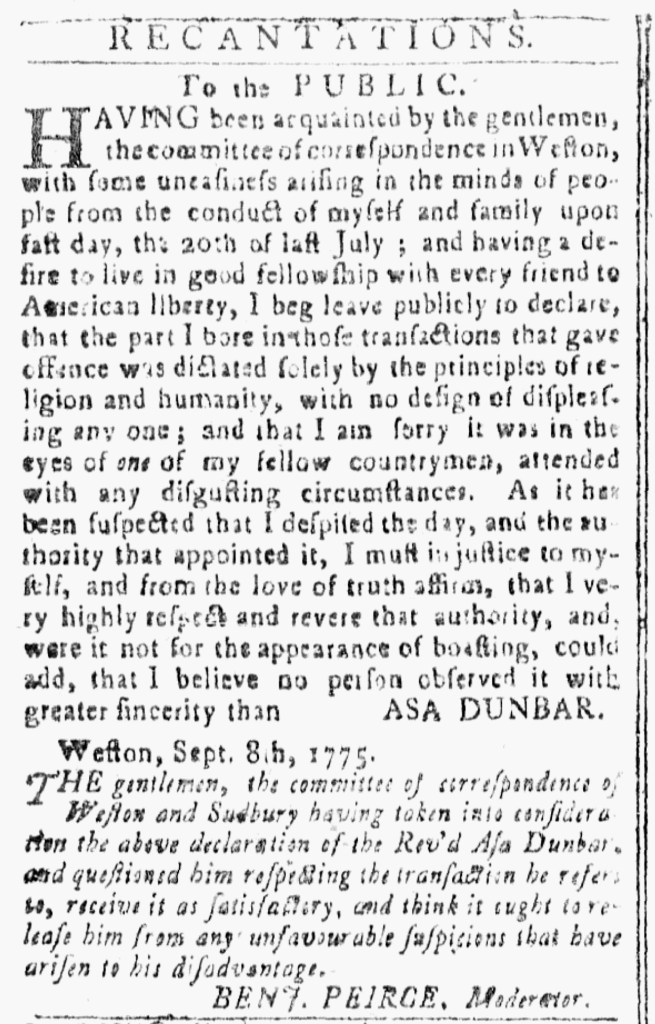

The final page of the September 21, 1775, edition of the New-England Chronicle had an entire column of “RECANTATIONS.” Five notices appeared under that header, four of them colonizers who expressed regret for signing an address to Thomas Hutchinson, the former governor of the colony, in February 1774. Such advertisements had become a regular feature in newspapers published in New England over the past year. In the first of the “RECANTATIONS,” however, Asa Dunbar, a minister in Salem, apologized for something else that had caused concern in his community.

He had been “acquainted by the gentlemen, the committee of correspondence in Weston” about “some uneasiness arising in the minds of people from the conduct of myself and family upon the fast day, the 20th of last July.” Katherine Carté, author of Religion and the American Revolution: An Imperial History, explains that on June 12 the Second Continental Congress passed a resolution to declare the fast on July 20, allowing for enough time for the news to reach distant colonies from Philadelphia. The fast day became, Carté asserts, “in effect our first national holiday.” Furthermore, it “was probably one of the only moments of the Revolutionary War that Americans experienced simultaneously, though not everyone celebrated it. In a short essay, “Why We Should Remember July 20, 1775,” she chronicles commemorations of the fast day throughout the colonies, noting that many embraced the occasion and a few “marked it in protest.”

Something happened that day that cast suspicion on Dunbar and his support for the American cause: “I beg leave publicly to declare, that the part I bore in those transactions that gave offence was dictated solely by the principles of religion and humanity, with no design of displeasing any one.” Whatever had occurred, the minister had not intended to make a statement, unlike Samuel Seabury who had “closed the doors of his church in protest” on the day of the fast. “As it has been suspected that I despised the day, and the authority that appointed it,” Dunbar proclaimed, “I must in justice to myself, and from the love of truth affirm, that I very highly respect and revere that authority.” Furthermore, “were it not for the appearance of boasting, [I] could add, that I believe no person observed it with greater sincerity.”

A short note from Benjamin Peirce, the moderator of Weston and Sudbury’s Committee of Correspondence, accompanied Dunbar’s recantation. He reported that the committee took into account Dunbar’s “declaration” and “questioned him respecting the transaction he refers to,” but he did not elaborate on that transgression. Whatever had occurred, the committee considered Dunbar’s explanation “satisfactory, and think it ought to release him from any unfavourable suspicions that have arisen to his disadvantage.” That must have been a relief to Dunbar. Like so many others, he resorted to an advertisement in the public prints to confess, to apologize, and to assure his community that he was not an enemy to American liberties.