What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

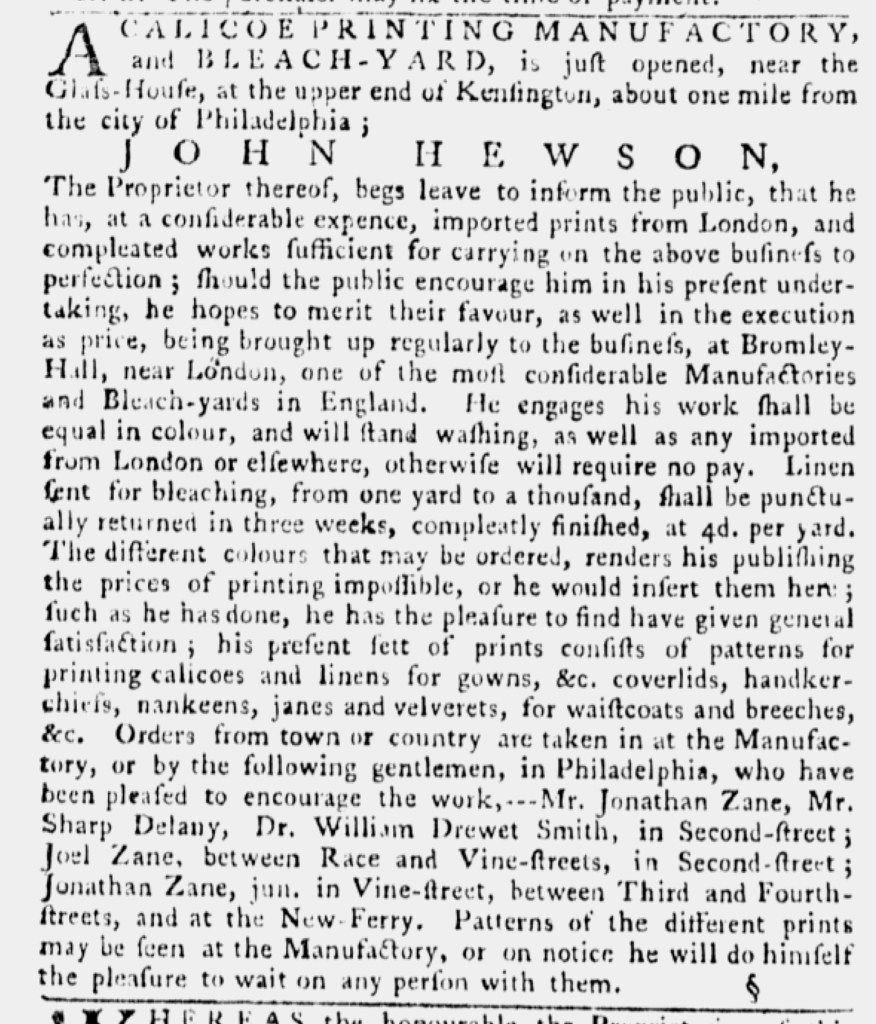

“Patterns of the different prints may be seen at the Manufactory.”

John Hewson joined the chorus of entrepreneurs promoting “domestic manufactures” or goods produced in the colonies as an alternative to imported goods when he announced that his “CALICOE PRINTING MANUFACTORY, and BLEACH-YARD, is just opened” on the outskirts of Philadelphia. As the imperial crisis intensified, it became more important than ever for producers and consumers in the colonies to unite in opposition to the “oppressive and arbitrary yoke” of a “corrupt and designing Ministry.” That was how an editorial addressed “To the INHABITANTS of the different COLONIES IN AMERICA” described current events. The following pages of the July 20, 1774, edition of the Pennsylvania Gazette featured a “SUMMARY of Monday’s DEBATES on the BOSTON BILLS” (or the Coercive Acts), “RESOLUTIONS unanimously entered into by the Inhabitants of SOUTH-CAROLINA, at a General Meeting, held at Charles-Town,” and updates from other colonies about how they intended to respond to the Boston Port Act.

That made it an opportune time for Hewson to promote his new enterprise, one that he assured consumers rivaled in quality his competitors on the other side of the Atlantic. At “considerable expence,” he had “imported prints from London, and completed works for carrying on [his] business to perfection.” In addition, he possessed valuable experience, having been “brought up regularly to the business, at Bromley-Hall, near London, one of the most considerable Manufactories and Bleach-yards in England.” Realizing that prospective customers may have been skeptical of his claims, Hewson offered a guarantee: “his work shall be equal in colour, and will stand washing, as well as any imported from London or elsewhere, otherwise will require no pay.” Customers had nothing to lose if Hewson did not charge for work that they found unsatisfactory. Furthermore, he charged reasonable prices for textile printing, though the extensive combinations of colors “renders his publishing the prices of printing impossible.” Hewson had a variety of patterns for customers to order. They could examine samples “at the Manufactory” or schedule appointments for Hewson to visit them. They could also place orders “at the Manufactory” or leave them with one of several associates “who have been pleased to encourage the work” and, in turn, endorsed the endeavor by partnering with Hewson in receiving orders.

Hewson did not directly mention the deteriorating relationship between the colonies and Britain nor proposals for new nonimportation agreements intended to harness commerce as political leverage. That hardly seemed necessary considering that readers almost certainly had current events in mind as they perused newspaper advertisements. Hewson did not need to belabor the political advantages of supporting his “CALICOE PRINTING MANUFACTORY” when news items and editorials already did that work.