What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“MEDICINES … at the Sign of the Lion and Mortar.”

Jonathan Waldo placed an advertisement for imported “DRUGS and MEDICINES” available at his shop on King Street in Salem, Massachusetts, in the Essex Gazette on April 11, 1775. He presumably paid a fee that included setting the type and running the notice in three consecutive issues before discontinuing it, a standard arrangement according to the pricing schemes in the colophons of several early American newspapers. That meant that his advertisement appeared again on April 18, the eve of the skirmishes at Lexington and Concord that started the Revolutionary War, and finally on April 25. That issue included coverage of “the Troops of his Britannick Majesty commenc[ing] Hostilities upon the People of this Province.” Samuel Hall and Ebenezer Hall would print only one more issue of the Essex Gazette in Salem before moving to Cambridge and continuing the newspaper as the New-England Chronicle. What happened to Waldo during the war? According to Donna Seger, the apothecary served as a major in the Salem Militia and his business “survived through the Revolution through a dual strategy of continuing to import apparently-contraband British medicine and concocting his own American substitutions.”

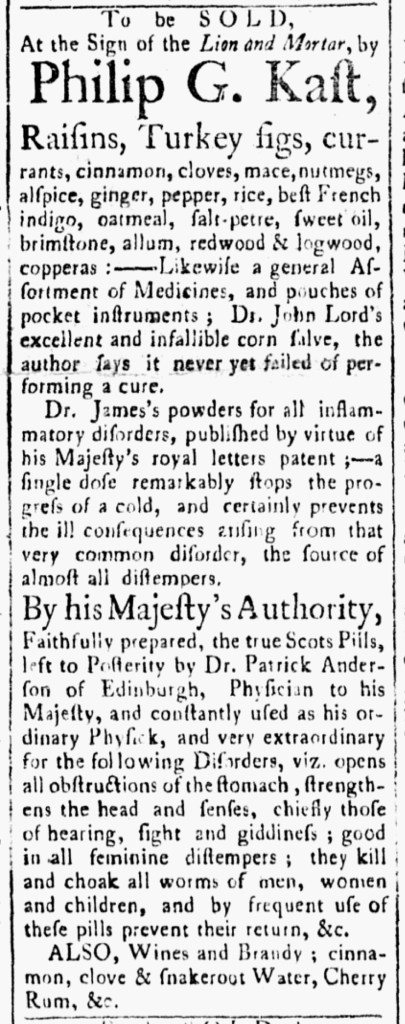

Seger describes Waldo as a savvy entrepreneur who diversified his business after the war, noting that “the Revolution seems to have inspired ‘innovation’ and reaped more profits” for the apothecary once he began marketing less expensive American versions of popular British patent medicines. His advertisement from the spring of 1775 indicates that he also made shrewd decisions before the war began, including setting up shop “at the Sign of the Lion and Mortar, lately improved by Dr. KAST.” Philip Godrid Kast was a well-known and successful apothecary who had marked his shop with “the Sign of the Lyon and Mortar” for many years. It almost certainly became a familiar sight for residents of Salem as they traversed the streets of the town and attracted notice from visitors. Kast even included an image of the sign on an engraved trade card dated to 1774, further associating the “Sign of the Lyon & Mortar” with his business when he distributed it to current and prospective customers. Waldo apparently took possession of the sign when he moved into the shop previously occupied by Kast. He could have commissioned a new device to represent his business. Nathaniel Dabney, for instance, sold medicines “at the Head of HIPPOCRATES, in Salem,” and included an illustration of the bust of the physician from ancient Greece in some of his advertisements. Yet the “Sign of the Lion and Mortar” was both appropriate for Waldo’s occupation and had a reputation associated with it that he wished to leverage. Waldo likely hoped to gain some of Kast’s customers when he took over the shop. Keeping the “Sign of the Lion and Mortar” on display testified to the continuity of service that he provided.