What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

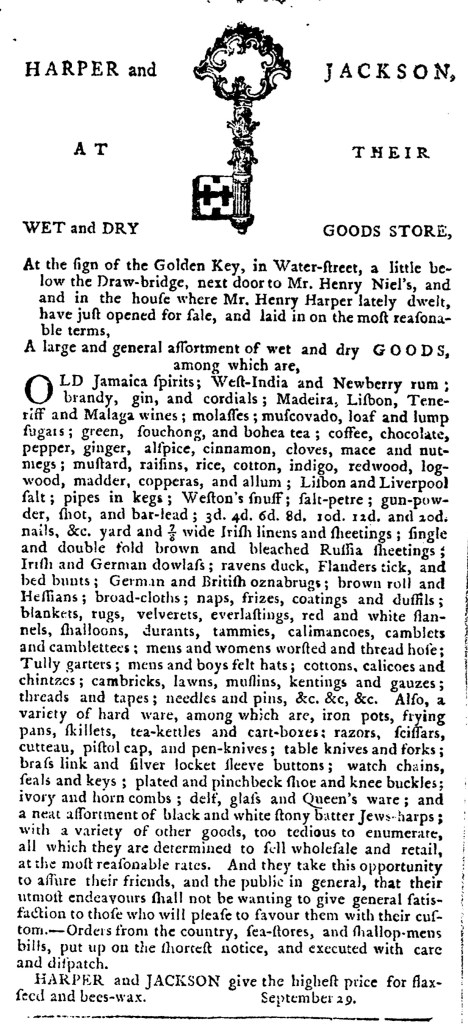

“At the Sign of the Golden Key.”

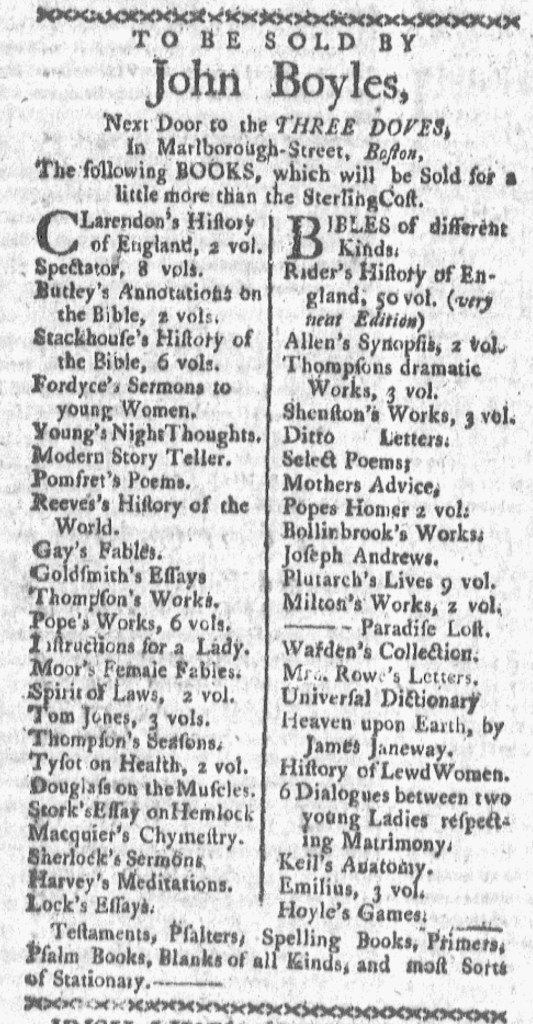

In the fall of 1773, William Ross, a shoemaker, informed readers of the Pennsylvania Journal that he imported a “Very neat assortment of BOOT LEGS and BEN LEATHER SOALS” and “double CALLIMANCOE for ladies shoes.” He asserted that he stocked “an assortment of the best articles in the business” for the benefit of “his friends and customers.” The copy for Ross’s advertisement occupied less space than the image that accompanied it. A woodcut depicting the sign that marked his location on Walnut Street included a shoe and the words “W. ROSS FROM SCOTLAND.” The shoemaker enhanced his advertisement by investing in a woodcut associated exclusively with his business, unlike the stock images of ships at sea included in some of the other advertisements on the same page.

Ross was not the only entrepreneur whose advertisement featured an image of a shop sign in the September 29 edition of the Pennsylvania Journal. Harper and Jackson adorned their notice for their “WET and DRY GOODS STORE, At the sign of the Golden Key” on Water Street with a woodcut of an ornate key. Their names flanked the key, further associating the device with their business. Unlike Ross, Harper and Jackson devoted most of their advertisement to copy, listing dozens of items among their inventory. In addition, they promised “a variety of other goods, too tedious to mention,” that they sold “at the most reasonable rates.” The merchants pledged “their utmost endeavours … to give general satisfaction to those who will please to favour them with their custom.” As much as prospective customers may have appreciated such appeals, it was likely the image of the key that initially attracted their attention to the advertisement and made it memorable.

These two advertisements testify to some of the advertising images that colonizers encountered as they navigated the streets of Philadelphia during the era of the American Revolution. Many merchants, shopkeepers, artisans, and tavernkeepers adopted, displayed, and promoted devices that became synonymous with their businesses, precursors to logos associated with corporations. Relatively few included images of their shop signs in their newspaper advertisements, though greater numbers did mention the symbols that marked their locations. Readers of the Pennsylvania Journal and other newspapers glimpsed truncated scenes of the commercial landscape of the bustling port as they perused the pages of the public prints.