What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Musick and Dancing.”

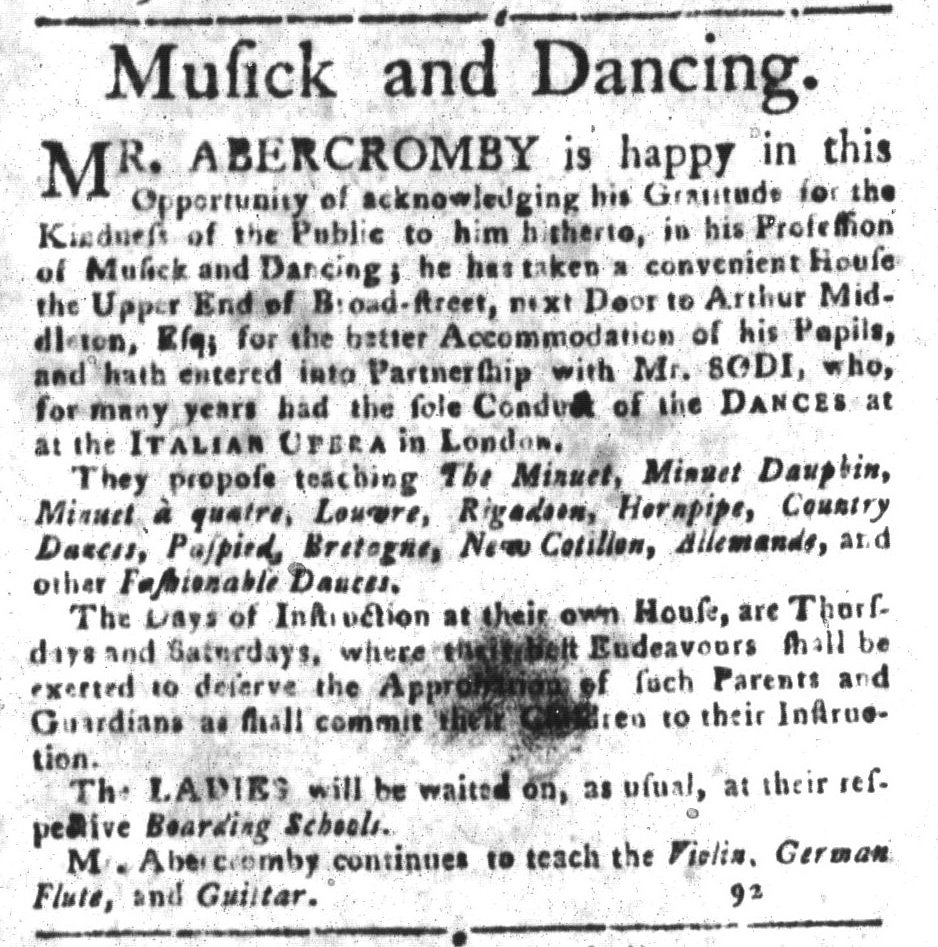

Among the advertisements for textiles, patent medicines, vessels preparing to depart for distant ports, and enslaved people for sale in the May 9, 1775, edition of the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal, Mr. Abercromby promoted lessons in “Musick and Dancing.” He started by expressing his appreciation for the support he already received, stating that he was “happy in this Opportunity of acknowledging his Gratitude for the Kindness of the Public to him hitherto, in his Profession.” Doing so bolstered his reputation; readers not previously familiar with Abercromby, especially genteel readers who knew that their social standing depended in part on their ability to demonstrate that they had mastered the steps of various dances or could play a musical instrument, may have asked themselves why they did not know Abercromby and whether they should make his acquaintance.

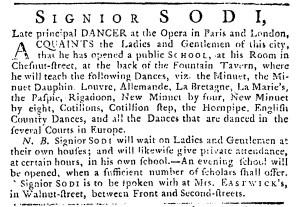

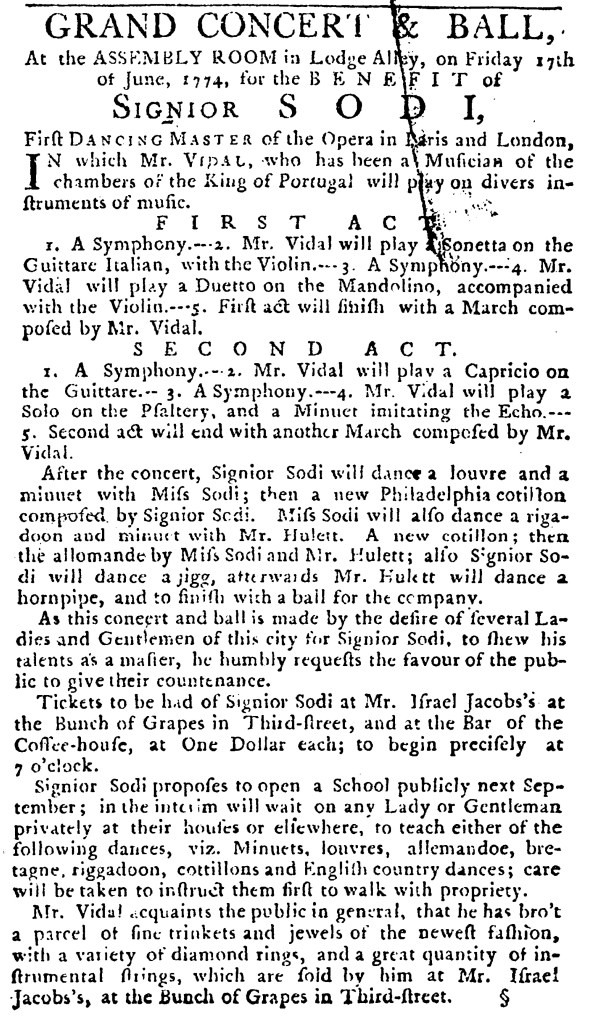

Abercromby next made two important announcements. First, he moved to a new location, a “convenient House [in] the Upper End of Broad-street” in Charleston, that offered “better Accommodation of his Pupils.” In addition, he “entered into Partnership with Mr. SODI, who, for many years had the sole Conduct of the DANCES at the ITALIAN OPERA in London.” Signior Sodi, as he styled himself, previously advertised his services in the Pennsylvania Journal in the summer and fall of 1774, but by the spring of 1775 he had migrated from Philadelphia to Charleston. Just as Sodi had done in his own advertisements, Abercromby emphasized the cachet of learning to dance from an instructor with connections to such an illustrious institution.

Abercromby listed nearly a dozen dances that he and Sodi taught, including “The Minuet, Minuet Dauphin, Minuet à quatre, Louvre, [and] Rigadoon,” as well as “other Fashionable Dances.” Their pupils could learn new dances or refine their steps for those they already knew. In addition to the lessons they gave at their “convenient House,” Abercromby and Sodi visited boarding schools in Charleston. Parents and guardians could arrange to enhance the curriculum that their young “LADIES” studied, trusting that the schoolmistresses provided appropriate supervision of the dancing masters and their pupils. Such services may have been especially attractive to the gentry in one of the largest and most cosmopolitan urban ports in the colonies. Abercromby and Sodi did not merely teach dancing, after all, but instead sold status to those who succeeded at their lessons.