GUEST CURATOR: Madeleine Arsenault

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Blue kersey.”

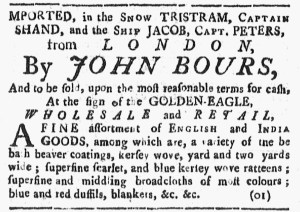

This advertisement offered a shipment from London of “beaver coatings,” fabrics, and blankets. John Bours sold all of these items at a shop that had a golden eagle on the sign. One of the specific items that Bours advertised was kersey, multiple colors of it even. After some research, I found that kersey was a fabric often used in making clothing for enslaved people. Talya Housman, a Ph.D. candidate at Brown University, places kersey with other fabrics in the category of “negro cloth” or “slave cloth.” Not only were these fabrics used to clothe enslaved people, but they were also used as a way “to mark people as enslaved.”

I also learned about slavery in New England. According to EnCompass: A Digital Sourcebook of Rhode Island History, “Rhode Island did not have the largest absolute number of enslaved people in New England,” but “it had the largest percentage of Africans, nearly all of them enslaved, among its residents.” In addition, about one half of all the ships in the triangular slave trade came through Rhode Island, making the colony one of the anchors on the American side of transatlantic trade. Rhode Island and other colonies in New England had more connections to slavery during the era of the American Revolution than I realized before my research.

**********

ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY: Carl Robert Keyes

Along with her peers in my Revolutionary America class in Fall 2023, Madeleine was responsible for contributing to both the Adverts 250 Project and the Slavery Adverts 250 Project. Through those projects, readings, and classroom discussions, we all learned more about the ubiquity of slavery throughout the colonies in the eighteenth century, including in New England, New York, Pennsylvania, and other places that most people do not readily associate with slavery. We examined a history of slavery well known to historians but often forgotten, intentionally overlooked, or stubbornly denied by many people.

In the course of her duties as guest curator for the Slavery Adverts 250 Project this week, Madeleine identified three advertisements about enslaved people that appeared in the January 31, 1774, edition of the Newport Mercury along with Bours’s advertisement. A notice on the front page offered a “STOUT, healthy Negro” woman for sale. On the final page, an advertisement seeking to sell a “LIKELY Negro” woman, “who understands all sorts of household work,” ran immediately to the left of Bours’s notice. Another notice, this one aiming to sell a “VERY likely, hardy NEGRO GIRL, about 15 years old,” or exchange her for a “NEGRO BOY,” appeared at the top of the column that contained Bours’s advertisement.

At first glance, an advertisement for a “FINE assortment of ENGLISH and INDIA GOODS,” including kersey cloth, may not seem to have much to do with slavery in New England. As she undertook her research, Madeleine made the connections, learning about both textiles used to clothe enslaved people and how the transatlantic slave trade contributed to commerce and consumer culture in Rhode Island before, during, and after the American Revolution. Bours was not alone in advertising imported goods; John Bell, Samuel Goldthwait, Thomas Green, George Lawton and Robert Lawton, Paul Mumford, and Jonathan Rogers placed similar advertisements. All of them participated in commercial networks inextricably bound to the transatlantic slave trade. Eighteenth-century readers knew that was the case. Advertisements offering enslaved people for sale that appeared alongside notices placed by merchants and shopkeepers served as a very visible reminder.