GUEST CURATOR: Megan Watts

Who was the subject of an advertisement in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

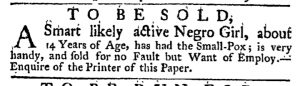

“TO BE SOLD, A Smart likely active Negro Girl.”

I chose this advertisement because it revolves around a controversial and pivotal part of early American society: slavery. In 1767, slavery was a part of life for British North American colonists everywhere. There were large workforces of slaves used to support Southern plantation agriculture. In addition, in other regions slaves were used on smaller scale farms and in domestic service. For the modern reader, the very contemplation of such practices is appalling and repulsive. However, we cannot look at American history without recognizing the integral role slavery played in society and the economy. Slavery also shaped American politics and government.

For instance, the founders focused on slavery during the Constitutional Convention in the summer of 1787, just twenty years after this advertisement was published. Over the course of the Constitutional Convention the delegates discussed multiple issues, including slave importation and whether proportional representation should include slaves. These were important issues that garnered differing opinions during the debates. The Northern states pushed for no representation of slaves to reduce Southern power, while Southerners fought to include slaves in their population.[1] Eventually, the delegates decided to count three out of five slaves in matters of representation; this was known as the Three-Fifths Compromise.[2] The debates about slavery characterized the Constitutional Convention and created intense tension. While the practice of slavery was abysmal, there was no doubt that it shaped the American Constitution and the government it established.

**********

ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY: Carl Robert Keyes

An anonymous slaveholder offered a “Smart likely active Negro Girl” for sale “for no Fault but Want of Employ.” In other words, the enslaved young woman evinced no shortcomings that prompted the sale. Instead, her owner simply did not have enough work to keep her busy and thus had no further use for her. Such explanations commonly appeared in advertisements offering single slaves for sale – both adults and youths – in New England and the Middle Atlantic colonies in the 1760s. This was a significant regional variation that distinguished many advertisements selling slaves in the northern colonies from their counterparts in the Chesapeake and Lower South.

“But Want of Employ” advertisements underscore the commodification of enslaved men, women, and children in eighteenth-century America. Slaveholders faced a choice when they determined that they no longer needed slaves’ labor: sell the slaves or set them free. The decision to sell them signals that slaveholders thought of their human property as any other commodity, an investment to be recouped as much as possible upon exceeding usefulness. A “Girl, about 14 Years of Age” could be traded as easily as textiles or furniture or any other goods that filled the advertising pages in colonial newspapers.

This advertisement and many more like it appeared in newspapers during the imperial crisis, the decade of tensions between colonists and Parliament that ultimately resulted in a war for independence. Colonists contemplated the meaning of liberty in their own lives even as they sold slaves “for no Fault but Want of Employ.” This advertisement makes clear that the promises of liberty were not evenly applied to all residents of the colonies during the transition from protest and resistance to severing political ties with Great Britain. This has been a central theme in my Revolutionary America course: many different kinds of experiences rather than a unified narrative.

As my students continue to curate the Slavery Adverts 250 Project they assess and verify this argument as they examine original sources. In many ways, a single advertisement for a “Smart likely active Negro Girl” to be “sold for no Fault but Want of Employ” is much more convincing than abstract statements that broadly aggregate the experiences of enslaved men, women, and children in the Revolutionary era.

**********

[1] Richard Beeman, Plain Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution (New York: Random House, 2009), 204-215.

[2] Beeman, Plain Honest Men, 204-215.