What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“The Managers of the American Manufactory … wish to employ every good spinner that can apply.”

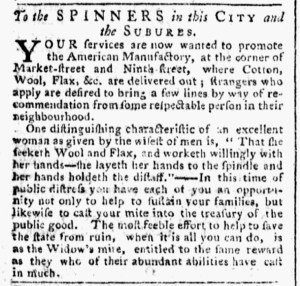

The proprietors of the American Manufactory in Philadelphia periodically took to the public prints to encourage the public to support their enterprise. In the March 1775, they called a general meeting at Carpenters’ Hall, the site where the First Continental Congress held its meetings the previous fall. They invited prospective investors to attend as well as sign subscription papers already circulating. A month later, the proprietors ran a brief advertisement, that one seeking both materials (“A Quantity of WOOL, COTTON, FLAX, and HEMP”) and workers “(a number of spinners and flax dressers”). That notice happened to appear in the Pennsylvania Journal on April 19, 1775, the day of the battles at Lexington and Concord, though it would take a while for residents of Philadelphia to learn about the outbreak of hostilities near Boston. The mission of the American Manufactory to produce an alternative to imported textiles became even more urgent. In August, the proprietors once again sought workers, publishing an address “To the SPINNERS in thisCITY and the SUBURBS.” They offered women an opportunity to participate in politics and “help to save the state from ruin.”

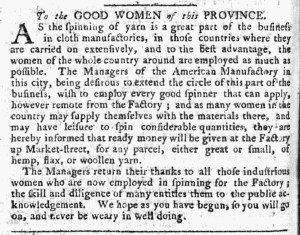

In November 1775, the proprietors or “Managers of the American Manufactory” made another appeal “To the GOOD WOMEN of this PROVINCE.” They explained that “the spinning of year is a great part of the business in cloth manufactories” and “in those countries where they are carried on extensively, and to the best advantage, the women of the whole country are employed as much as possible.” Having already engaged women “in this CITY and the SUBURBS” who responded to their previous advertisement and apparently needing even more yarn to make into textiles, the managers found themselves “desirous to extend the circle … to employ every good spinner than can apply, however remote from the Factory.” They believed that women in the countryside “may supply themselves with the materials there” and had “leisure to spin considerable quantities.” They may have been right on the first count, but perhaps overestimated how many other responsibilities wives, mothers, sisters, and daughters had in their households. For those who made the time, the managers offered “ready money … for any parcel, either great or small, of hemp, flax, or woollen yarn.”

The managers also lauded the contributions of “those industrious women who are now employed in spinning for the Factory,” declaring that “the skill and diligence of many entitles them to the public acknowledgement.” They served the American cause in their own way according to their own abilities, just as the delegates to the Second Continental Congress did and just as the soldiers and officers participating in the siege of Boston did. “We hope as you have begun,” the managers encouraged, “so you will go on, and never be weary in well doing.”