What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“MAKES and sells soap and candles … for exportation.”

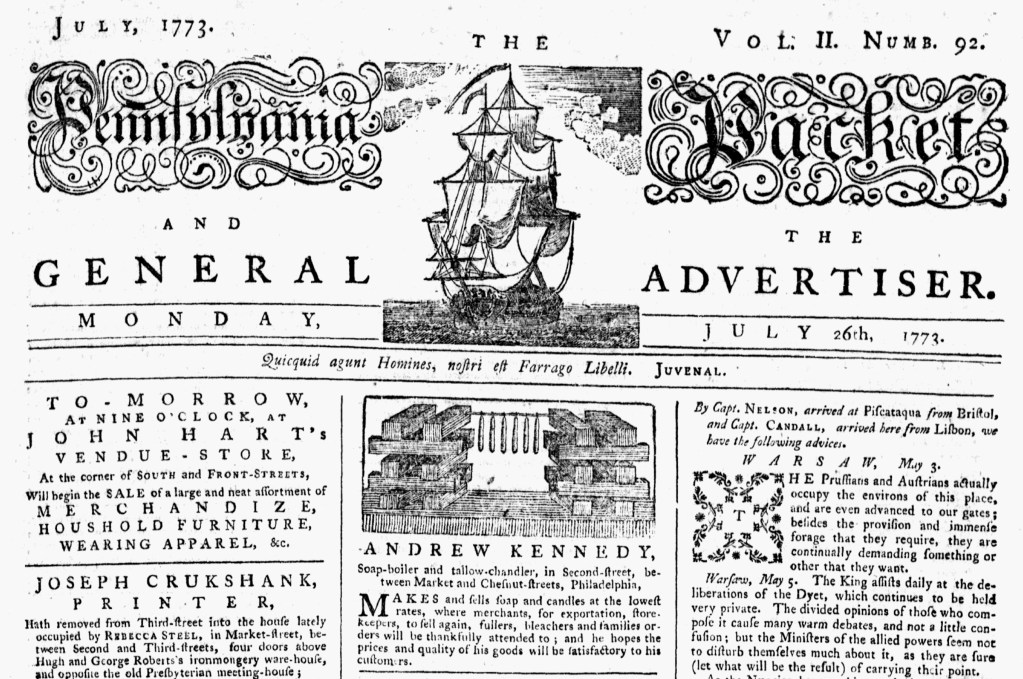

The front page of the July 26, 1773, edition of the Pennsylvania Packet and General Advertiser featured two images. As usual, a woodcut depicting a ship at sea appeared in the masthead. The newspaper took its name from the packet ships that crisscrossed the Atlantic, transporting passengers and freight. Significantly, packet ships also carried information, whether written in letters, printed in newspapers, or shared by captains, other officers, and crew. The Pennsylvania Packet, like a packet ship, disseminated news to every destination it reached. Whether accounts of current events, rosters of vessels arriving and departing from customs houses, prices current for commodities, or advertisements, the contents of the Pennsylvania Packet facilitated commerce in Philadelphia, its figurative home port, and readers wherever they happened to peruse the newspaper.

Andrew Kennedy certainly hoped that the Pennsylvania Packet and General Advertiser would facilitate his own commercial interests. The “soap-boiler and tallow-chandler” ran a shop in Philadelphia, though he aimed to serve consumers far beyond that bustling port. Like packet ships and newspapers, he envisioned the soap and candles that he made and sold “at the lowest rates” reaching faraway places. He offered them to “merchants, for exportation,” and to “storekeepers, to sell again,” presenting those options for buying by volume first before mentioning “families orders.” Like many other artisans and shopkeepers who advertised in colonial newspapers, he promoted the “prices and quality of his goods” and concluded with overtures about customer satisfaction. Kennedy commenced his advertisement with an image that readers immediately recognized, stacks of blocks on the right and left to support a string dangling six freshly-dipped candles. Without even skimming the rest of the advertisement, readers knew that Kennedy sold candles.

Only two other images appeared in that issue of the Pennsylvania Packet, both of them woodcuts of indentured servants who ran away from their masters. John Dunlap, the printer, provided those stock images to the advertisers, but Kennedy commissioned a woodcut for his own exclusive use. That image likely helped attract attention to the appeals to price and quality that he intended to resonate with merchants, shopkeepers, and other prospective customers.