What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“AN assortment of ENGLISH GOODS … too numerous to particularize.”

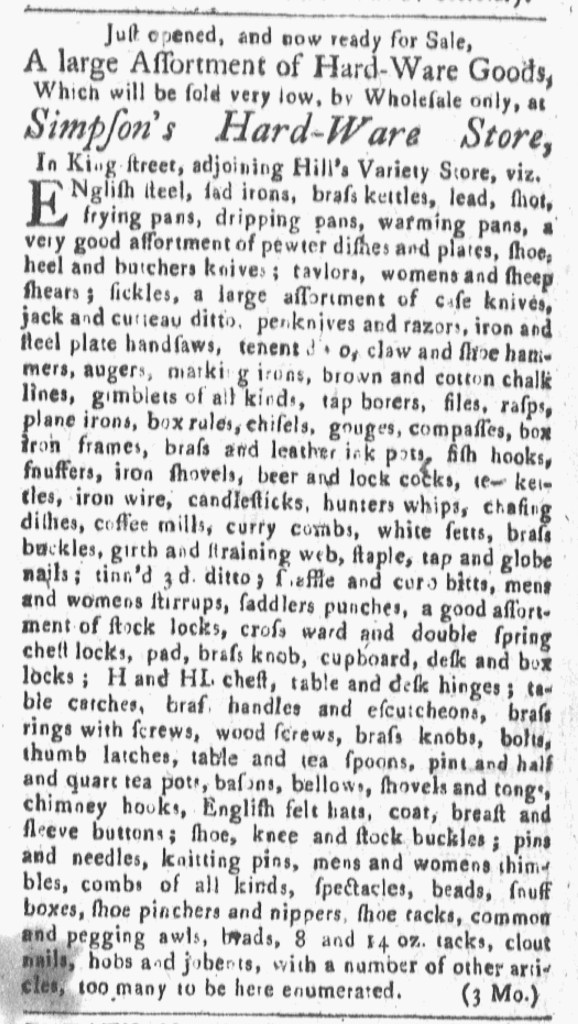

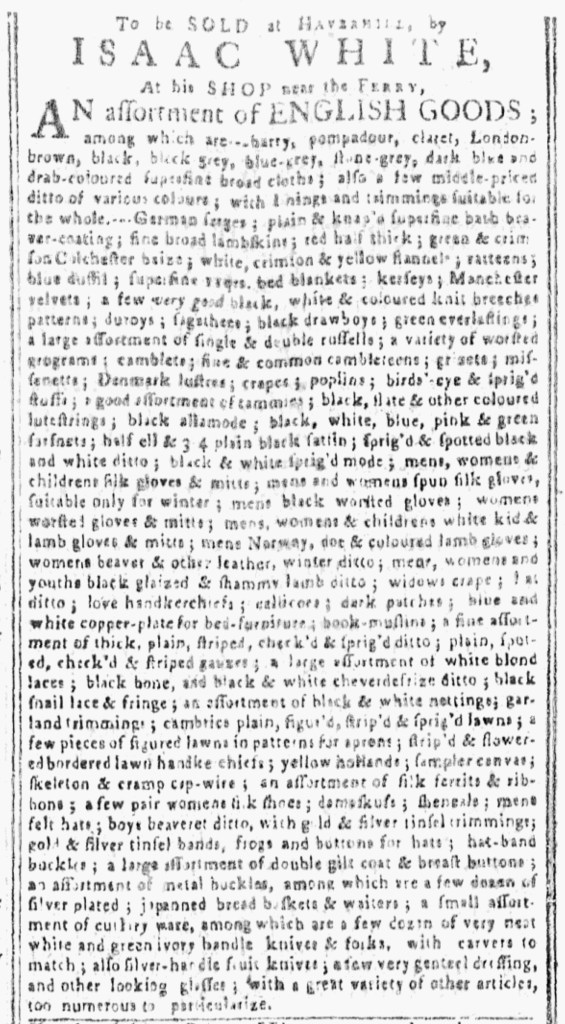

Isaac White placed an advertisement for an “assortment of ENGLISH GOODS” available at “his SHOP near the FERRY” in Haverhill, Massachusetts, in the December 28, 1775, edition of the New-England Chronicle. Despite the outbreak of hostilities at Lexington and Concord eight months earlier and the Continental Association remaining in effect, his advertisement looked much like those that so frequently appeared in American newspapers at times when colonizers did not attempt to use nonimportation agreements as political leverage in their contest with Parliament. White listed dozens of items, including many varieties and colors of textiles, ribbons, “a large assortment of double gilt coat & breast buttons,” “a few very genteel dressing, and other looking glasses,” and “a small assortment of cutlery ware, among which are a few dozen of very neat white and green ivory handle knives & forks, with carvers to match.” As if that was not enough, White concluded his catalog with a promise of “a great variety of other articles, too numerous to particularize.”

The shopkeeper did not mention when he acquired his merchandise, whether all those items arrived in the colonies before the Continental Association went into effect, yet he did rely on a familiar marketing strategy by presenting readers with an array of choices and inviting them to imagine themselves visiting his shop, examining his inventory, selecting the goods they desired, and displaying their style and taste to others after they made their purchases. Consumption certainly had political dimensions during the imperial crisis, but even after the Revolutionary War began habits that had developed (and that advertisers like White had helped in cultivating) did not easily fade. In the same issue of the New-England Chronicle, Martin Bicker ran an advertisement about a “fresh supply” of “ENGLISH GOODS … just received from New-York and Philadelphia … now selling off at his store in Cambridge.” Though not as extensive as White’s notice, Bicker’s advertisement listed several kinds of textiles and handkerchiefs. It concluded with “&c. &c. &c.” Repeating the common abbreviation for et cetera made the same promise of even more items as White’s assertions about “a great variety of other articles, too numerous to particularize.” In addition, Bicker declared, “Those that intend to purchase must speedily apply, otherwise they will be disappointed.” He expected to do brisk business.

That colonizers continued consuming during the Revolutionary War does not necessarily merit attention. After all, people needed goods. Then as now, warfare disrupted commerce but did not eliminate it. Yet the advertisements placed by White and Bicker did not suggest that they served customers who merely sought to purchase necessities. Instead, they continued to cater to the desires of consumers who continued to shop for many of the reasons they did before the war began. Some may have had a new purpose, seeking distractions from current events. How readers responded, these advertisements do not reveal, yet they do indicate that White and Bicker saw opportunities for business as usual.