What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

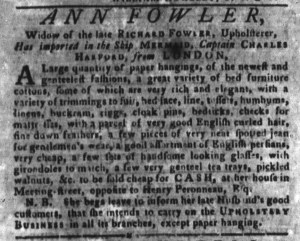

“She intends to carry on the UPHOLSTERY BUSINESS in all its branches, except paper hanging.”

Ann Fowler, “Widow of the late RICHARD FOWLER, Upholsterer,” took to the pages of the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal to advertise a variety of merchandise that she sold out of her house on Meeting Street in Charleston. She indicated that she imported her wares “in the Ship MERMAID, Captain CHARLES HARFORD, from LONDON,” a vessel that arrived in port on December 29, 1774, according to the list of “ENTRIES INWARDS” at the custom house published in the January 3, 1775, edition of the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal. Those goods should have fallen under the jurisdiction of the Continental Association. Nevertheless, Fowler hawked a “Large quantity of paper hangings, of the newest and genteelest fashions, a great variety of bed furniture cottons, some of which are very rich and elegant, with a variety of trimmings to suit, [and] a few sets of handsome looking glasses, with girandoles to match.” The widow was not the only advertiser who placed notices about imported goods that looked the same as those published before the Continental Association went into effect.

Fowler appended a nota bene to “inform her late Husband’s good customers, that she intends to carry on the UPHOLSTERY BUSINESS in all its branches, except paper hanging.” Widows often took over the family business in colonial America, sometimes doing the same tasks their husbands had done and sometimes supervising employees. Even though Ann had not been the public face of the enterprise while Richard still lived, she likely had experience assisting him in his shop and interacting with any assistants that he hired. She hoped that she and her husband had cultivated relationships that would allow her to maintain their clientele, though they would have to look elsewhere when it came to “paper hanging” or installing wallpaper. Fowler sold papers hangings “of the newest and genteelest fashions,” but her customers needed to contract with someone else to paste them up. That may have been because she lacked experience with that aspect of the family business, her role having been primarily in the shop. On the other hand, perhaps she felt comfortable doing all sorts of upholstery work in the shop, a semi-public space that now belonged to her, but she did not consider it appropriate to enter the private spaces of her customers, especially male clients who lived alone. As a female entrepreneur, Fowler may have attempted to observe a sense of propriety that the public would find acceptable. Whether or not Fowler had prior experience installing paper hangings, she constrained herself in discontinuing that service following the death of her husband.