What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“A new edition of COMMON SENSE … with large and interesting additions by the author.”

A battle over publishing Thomas Paine’s Common Sense played out in advertisements became apparent to the public when they perused the advertisements in the January 25, 1776, edition of the Pennsylvania Evening Post. Sixteen days earlier, that newspaper had been the first to carry an advertisement for the inflammatory political pamphlet. Robert Bell, the publisher, promoted it, while Paine remained anonymous. It sold so quickly that Bell began advertising “A NEW EDITION of COMMON SENSE” on January 20. Five days later, he ran an updated version of the original advertisement, using type already set. The compositor merely replaced the first line, removing the date (“Philadelphia, January 9, 1776”) and replacing it with a headline that proclaimed, “The second edition,” in a larger font.

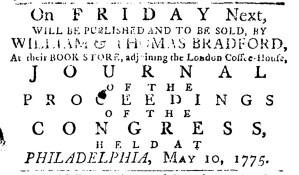

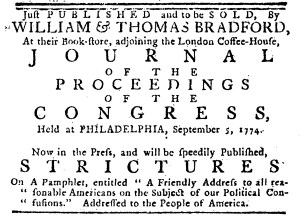

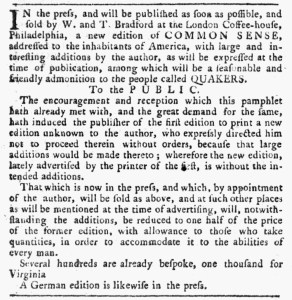

Yet Paine and Bell had had a falling out. Bell’s “second edition” was an unauthorized edition, as a new advertisement on the first page of the Pennsylvania Evening Post made clear. William Bradford and Thomas Bradford, printers of the Pennsylvania Journal, announced that they had a “new edition” of Common Sense “IN the press, and will be published as soon as possible.” Unlike Bell’s second edition advertised elsewhere in that issue, their new edition featured “large and interesting additions by the author, as will be expressed at the time of publication.” As a preview, the Bradfords indicated that the bonus materials included a “seasonable and friendly admonition to the people called QUAKERS.” To entice prospective customers to reserve copies or purchase them as soon as they were available, the Bradfords noted that “Several hundred are already bespoke,” including “one thousand for Virginia.” Advertisements for the pamphlet already appeared in newspapers in New York. The Bradfords made plans to distribute the pamphlet south of Philadelphia. In addition, they reported that a “German edition is likewise in the press” for the benefit of the many German settlers in Pennsylvania and the backcountry extending down to North Carolina.

This advertisement included an address “To the PUBLIC,” perhaps composed by Paine, that outlined the dispute between the author and the original publisher. “The encouragement and reception which this pamphlet hath already met with, and the great demand for the same,” the address declared, “hath induced the publisher of the first edition to print a new edition unknown to the author.” Paine had “expressly directed him not to proceed therein without orders, because that large additions would be made hereto.” He also did not appreciate that Bell had not managed to turn a profit on the first edition, though that did not receive mention in the address in the advertisement. Readers needed to be aware that Bell’s new edition, “lately advertised by the printer of the first [edition], is without the intended additions.” That being the case, readers who exercised a little patience for the Bradfords’ edition “now in the press” and authorized by the author could acquire both the contents of the original pamphlet and the additions in a single volume … and at a bargain price! Even with the new material, the cost “will … be reduced to one half of the price of the former edition.” Bell advertisements consistently listed “two shillings” for the pamphlet. The Bradfords charged one shilling. They also gave “allowance to those who take quantities” or a discount for purchasing in volume, either to retail or distribute to friends, family, and associates. That would “accommodate [the pamphlet] to the abilities of every man.” In other words, the lower price made it possible to disseminate Common Sense even more widely. When it came to airing grievances over the publication of Common Sense in newspaper advertisements, this address “To the PUBLIC” was only the opening salvo. The dispute continued in subsequent editions of the Pennsylvania Evening Post and other newspapers.