What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

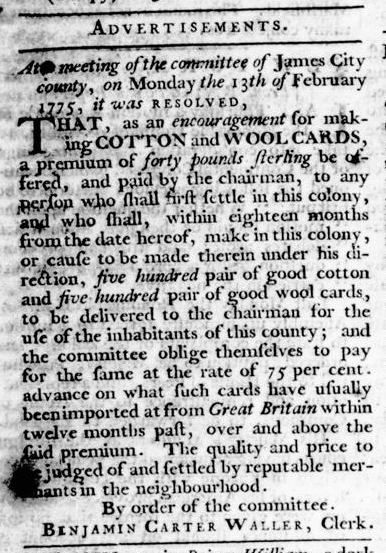

“An encouragement for making COTTON and WOOL CARDS … in this colony.”

Residents of James City County took the Continental Association seriously, especially the eighth article. When the First Continental Congress devised that nonimportation, nonconsumption, and nonexportation agreement in response to the Coercive Acts, they included an article that called for colonizers “in our several Stations, [to] encourage Frugality, Economy, and Industry; and promote Agriculture, Arts, and the Manufactures of this Country, especially that of Wool.” In turn, the “committee of James City county” passed a resolution for the “encouragement for making COTTON and WOOL CARDS” at its meeting in February 1775.

Within days an advertisement appeared in Alexander Purdie’s Virginia Gazette and John Dixon and William Hunter’s Virginia Gazette to inform enterprising entrepreneurs that the committee offered “a premium of forty pounds sterling … to any person who shall first settle in this colony, and who shall, within eighteen months from the date hereof, make in this colony, or cause to be made therein under his direction, five hundred pair of good cotton and five hundred pair of good wool cards … for the use of the inhabitants of this county.”

Preparing wool and cotton for spinning involved separating and straightening the fibers using two cards or paddles with fine wire teeth. That process made wool and cotton easier to spin; it also made the cards an essential tool for producing textiles as alternatives to imported fabrics. While the committee assumed that men would make the cards, it would be women who used them. That gave political meaning to the activities they undertook in carding, spinning, and weaving, just as women participated in politics when they refused to purchase imported cards, imported textiles, or any other imported goods.

Making cotton and wool cards in Virginia had the potential to be a profitable venture. In addition to the premium, the committee offered a “75 per cent. advance on what such cards have usually been imported at from Great Britain within the twelve months past.” In other words, the committee agreed to pay nearly twice what importers had recently paid for this important tool, another incentive for producing cards in the colony.

Supporters of the American cause had already mobilized in boycotting imported goods and producing alternatives. This advertisement suggested one more means of contributing to those efforts, making cotton and wool cards in Virginia. A successful venture would have ripple effects as women purchased those cards and used them in processing cotton and wool to produce homespun cloth rather than buying imported textiles. The premium offered for making cotton and wool cards was part of a larger project with significant political implications.