GUEST CURATOR: Shannon Holleran

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“Powder horns.”

The “Powder horns” near the end of Joseph and William Russell’s full-page advertisement made me curious. I discovered that a powder horn was used for holding gun powder (which the Russells also sold).

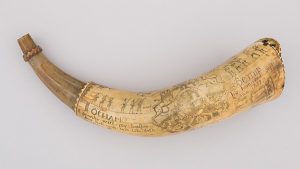

Many powder horns from this period have intricate engravings on them. Some people took up horn carving as an occupation. One of the best-known horn carvers of this time period was Jacob Gay, who often carved his initials onto the powder horns he created. Historians are now able to spot the artwork he created by the “J G” engraved on a powder horn.

Many powder horns have specific styles based on the period they were made and the battles that occurred at that time. Powder horns decorated just before and during the American Revolution often indicated New England’s anti-British feelings. Also, many of the engraved horns depicted battles fought during the Revolution. In addition to being used to reflect battles, powder horn engravings were also expressive of camp life during the Revolution.

In the midst of the Revolution, many powder horns were also used as forms of identification. Following the Battles of Lexington and Concord, many soldiers began engraving their names or initials on their powder horns. As a result, historians are now able to identify many of the soldiers who fought in battles of the Revolution.

For more information and examples, see William H. Guthman’s “Powder Horns Carved in the Provincial Manner, 1744-1777.”

**********

ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY: Carl Robert Keyes

Joseph and William Russell’s full-page advertisement, the first published in the Providence Gazette, first appeared three months earlier, on November 22, 1766. Since then, it ran multiple times, either because the Russells were keen on advertising or because Mary Goddard and Company needed any sort of content to fill the pages when faced with the combination of a dearth of new paid notices and post riders carrying news from other colonies chronically arriving too late for any of it to appear in the current issue. As a result, residents of Providence and readers of the newspaper printed there were exposed to the Russells’ full-page advertisement on many occasions.

Due to the prominence and frequency it appeared in late 1766 and early 1767, this advertisement has also reappears fairly regularly as a point of reference when examining other paid notices in the Providence Gazette – or trying to explain the absence of those notices. While the methodology for the project, when strictly observed, prohibits featuring this advertisement a second time, there’s room for making exceptions when doing so yields productive observations about advertising practices and consumer culture in eighteenth-century America.

Shannon is the first student in my Revolutionary America class to take on responsibilities for guest curating the Adverts 250 Project. In turn, this is the first time students in that class have encountered the Russells’ advertisement, giving us an opportunity to discuss what was possible when it came to advertising in the revolutionary era compared to what was much more common. Revisiting this advertisement serves a second pedagogical purpose. For her work in preparing today’s entry, Shannon considered the variety of goods listed in this lengthy advertisement before choosing one to examine in greater detail. In the end, she took a closer look at an item not previously incorporated into the Adverts 250 Project, simultaneously expanding her own knowledge about an aspect of early American material culture and enhancing the project.

Finally, by choosing this advertisement Shannon contributes to an ongoing analysis of the advertising content of the Providence Gazette. This advertisement repeatedly occupied one-quarter of the space in any issue in which it appeared, quite a bit of space for the printers to yield. As mentioned above, Goddard and Company seemed to have difficulty attracting advertisers, especially when comparing their newspaper to counterparts published in Boston, Charleston, New York, and Philadelphia. That is a story that could not be told if the Russells’ full-page advertisement were permanently excluded from further consideration simply because the Adverts 250 Project previously featured it.