What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“New-England Rum and Melasses, Claret and Lisbon Wine.”

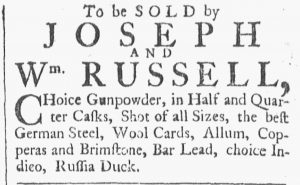

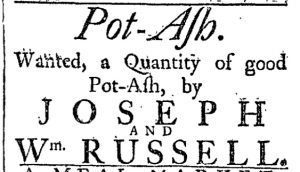

Joseph Russell and William Russell regularly advertised in the Providence Gazette in the 1760s and 1770s. In the spring of 1774, the merchants inserted a notice that listed a variety of commodities, including “Jamaica and Barbados Rum, New-England Rum and Melasses, Claret and Lisbon Wine, Coffee, Sugar, Indico, Alspice, large Rock Salt, [and] choice Connecticut Beef and Pork, in Barrels and Half Barrels.” They did not happen to include tea among their inventory, at least not among the items they enumerated in their newspaper advertisement, even though they frequently stocked it in the past. Just over a year earlier, they led one of their advertisements with “Excellent Bohea Team, which for Smell and Flavor exceeds almost any ever imported, by the Chest, Hundred, or dozen Pounds.” Perhaps the crisis around tea – the Boston Tea Party and the efforts of the Sons of Liberty to turn away ships carrying tea in other port cities – convinced them not to advertise that commodity. As they often did, the Russells concluded with a promise of various “English and Hard-Ware Goods.”

Compared to many of the advertisements they ran in the 1760s, their notices became more restrained in the 1770s. Their advertisement for the spring of 1774 filled the standard “square,” roughly equivalent in length to most other paid notices in the Providence Gazette. In contrast, their advertisement in the March 19, 1768, edition listed dozens of items. The Russells demonstrated that “their assortment is very large” and “customers will have the advantage of a fine choice” with an advertisement that extended more than a column. On previous occasions, they ran full-page advertisements, including in the November 22, 1766, and November 7, 1767, editions of the Providence Gazette. Many of their advertisements from the 1760s tended to look like the one for “HILL’s ready Money Variety Store” that appeared in the spring of 1774. Why did the Russells opt for less elaborate advertisements when facing such competition? Perhaps they felt secure in their reputation, deciding that shorter notices made customers sufficiently aware of their merchandise. In 1772, the prominent merchants built “the second brick edifice and the first three-story structure in Providence,” making them and their business even more visible to residents of the growing port. As their wealth increased and their status reached new heights, the Russells had other means of attracting attention to their enterprise beyond newspaper advertisements, yet they still considered streamlined notices valuable investments in advancing their entrepreneurial activities.