What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“UMBRILLOES.”

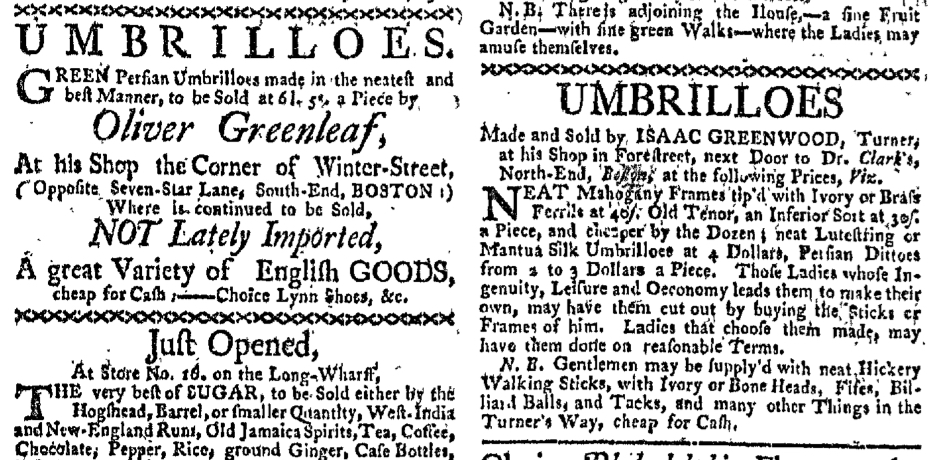

Oliver Greenleaf and Isaac Greenwood placed competing advertisements for “UMBRILLOES” in the June 12, 1769, edition of the Boston-Gazette. They relied on different marketing strategies, but both presented umbrellas as accessories perfectly appropriate for colonists, especially women, to acquire and use. Kate Haulman explains that umbrellas were a source of debate in the era of the American Revolution. They had only recently appeared in England and its colonies in North America. “Though large and clumsy by modern standards,” Haulman explains, “the umbrellas of the late eighteenth century were brightly colored items of fashion made of oiled silk, stylistic spoils of empire hailing from India.” Yet some colonists were uncertain that they should adopt this fashion. Beyond the space devoted to advertising, debates about umbrellas appeared elsewhere in colonial newspaper, “the forum best suited to prescribe or proscribe certain styles and behaviors for a wide audience of readers.” Some colonists considered umbrellas “ridiculous and frivolous, serving no purpose that a good hat could not supply.” Others allowed for their use, but only by women. In the eighteenth-century, many considered the umbrella a feminine accessory.[1]

Other colonists, however, defended umbrellas. Greenleaf and Greenwood addressed them, though they likely hoped to win new converts with their advertisements as well. Greenleaf did not acknowledge the debate over umbrellas. Instead, he positioned his umbrellas and the “great Variety of English GOODS” available at his shop within another debate about consumer culture. He proclaimed that his umbrellas and other goods were “NOT Lately Imported.” Usually merchants and shopkeepers emphasized that they carried the latest fashions that only recently arrived via ships from English ports, but in 1769 the vast majority in Boston participated in a nonimportation pact in protest of the duties on certain goods imposed by the Townshend Acts. A committee of merchants and traders monitored adherence and published reports in the city’s newspapers. Greenleaf’s livelihood and his reputation both depended on assuring the public that he did not peddle goods that violated the nonimportation agreement, hence his assertion that his merchandise was “NOT Lately Imported.”

Prospective customers interested in making purchases from Greenwood, on the other hand, did not need to worry about when he had acquired his umbrellas because he made them at his shop in the North End of Boston. Along with the nonimportation agreement, merchants, shopkeepers, and other colonists emphasized the importance of local production, what they termed domestic manufactures, coupled with virtuous consumption of goods produced in the colonies. This required the commitment of both suppliers and consumers. As a producer, Greenwood fulfilled the first part; he depended on consumers to do their part by choosing his umbrellas over those imported by Greenleaf, regardless of when they might have been transported across the Atlantic. He did imply that women might be more interested in umbrellas than men when he addressed “Ladies whose Ingenuity, Leisure and Oeconomy leads them to make their own.” They could save some money and demonstrate their own industry by purchasing the materials – fabrics and “Sticks or Frames” – from Greenwood and then putting together the umbrellas on their own. Although Greenleaf more explicitly commented on the nonimportation agreement then in effect, Greenwood more effectively placed his umbrellas within the discourse of local production.

Umbrellas were the subject of several debates and controversies in the decade before the American Revolution. Some colonists questioned their use at all, depicting them as unnecessary luxuries and frivolous feminine accessories. Others advocated for umbrellas, but only those that did not violate the terms of the nonimportation agreements. Those produced in local workshops possessed even greater cachet. In that regard, umbrellas became imbued with political as well as cultural meaning.

**********

[1] Kate Haulman, “Fashion and the Culture Wars of Revolutionary Philadelphia,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser., 62, no. 4 (October 2005): 632.