What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Numbers have promised they would subscribe that have not sent in their names.”

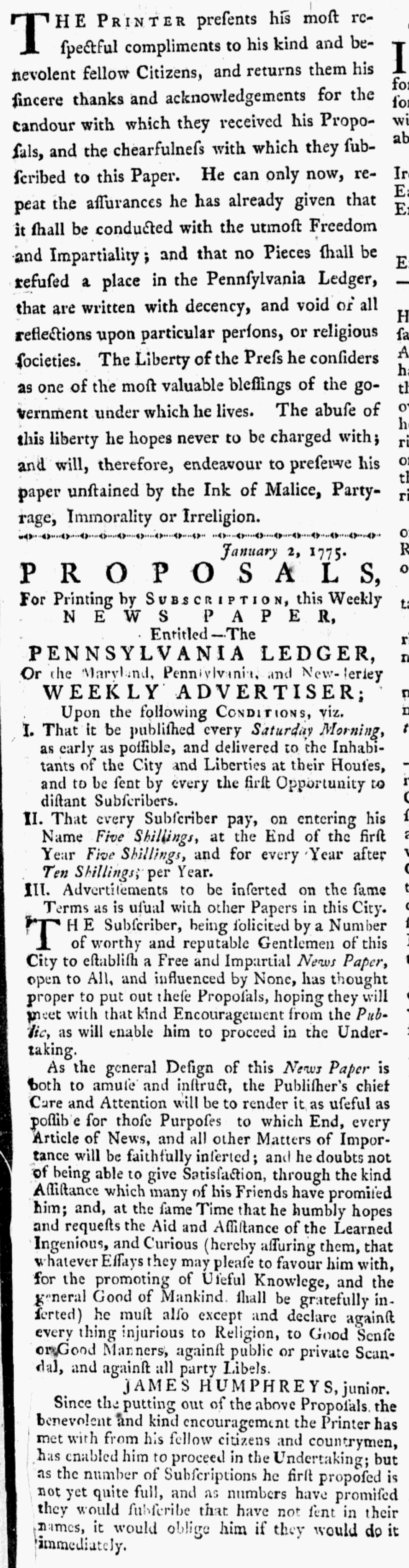

The second issue of the Pennsylvania Ledger began with the same notice from the printer, James Humphreys, Jr., that appeared as the first item in the first column on the first page of the inaugural issue a week earlier. He apparently considered it worth running again, especially since the new publication had not yet achieved as wide a circulation as he hoped. Humphreys’s message to “his kind and benevolent fellow Citizens” thus bore repeating to reach as many readers (and prospective subscribers) as possible as copies of Philadelphia’s newest newspaper found their way into coffeehouses and taverns or passed from hand to hand.

In that address, the printer “repeat[ed] the assurances he has already given” in proposals for the newspaper “that it shall be conducted with the utmost Freedom and Impartiality; and that no Pieces shall be refused a place in the Pennsylvania Ledger, that are written with decency, and void of all reflections upon particular persons, or religious societies.” Printers often asserted that their publications would represent multiple perspectives when they addressed the public in the decade before the Revolutionary War, though many did not follow through on that promise. Some privileged their own political views while others responded to what they perceived to be the overwhelming sense (or the most vocal voices) in the communities where they operated their printing presses. In his subscription proposals, Humphreys promoted a “FREE and IMPARTIAL” newspaper. In his monumental History of Printing in America (1810), Isaiah Thomas acknowledged that Humphreys purported to publish an impartial newspaper, yet “[i]t was supposed that Humphrey’s paper would be in the British interest” and the Pennsylvania Evening Post, founded by Benjamin Towne at the same time, “took the opposite ground.”[1] In his address, Humphreys proclaimed that he considered “Liberty of the Press … one of the most valuable blessings of the government under which he lives,” though his ideas about what constituted “Liberty of the Press” may have differed from that of other colonizers. As the imperial crisis intensified, more and more newspapers became associated with either Patriots or Loyalists.

Still, Humphreys wanted to make a go of it with the Pennsylvania Ledger. In that second issue, he inserted the proposals immediately below his address to the public, filling the remainder of the column. He explained in even more detail that “the general Design of this News Paper is both to amuse and instruct” so “every Article of News, and all other Matters of Importance will be faithfully inserted.” In billing his newspaper as “Free and Impartial,” Humphreys may have intended to make a point that readers should expect to encounter pieces representing a variety of views, but, as Thomas suggested, many were suspicious of Humphreys’s intentions when it came to disseminating content from the Tory perspective. That could have contributed to a note that the printer added to the proposals. He claimed that he received enough “encouragement … to proceed in the Undertaking,” but “numbers have promised they would subscribe that have not sent in their names.” As they learned more about the positions the Pennsylvania Ledger would likely take, some prospective subscribers apparently decided they did not wish to support the newspaper.

**********

[1] Isaiah Thomas, The History of Printing in America: With a Biography of Printers and an Account of Newspapers (1810; New York: Weathervane Books, 1970), 399.

[…] he launched the Pennsylvania Ledger in the winter of 1775, James Humphreys, Jr., distributed proposals declaring that it would be a “Free and Impartial News Paper, open to All, and Influenced by […]