What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

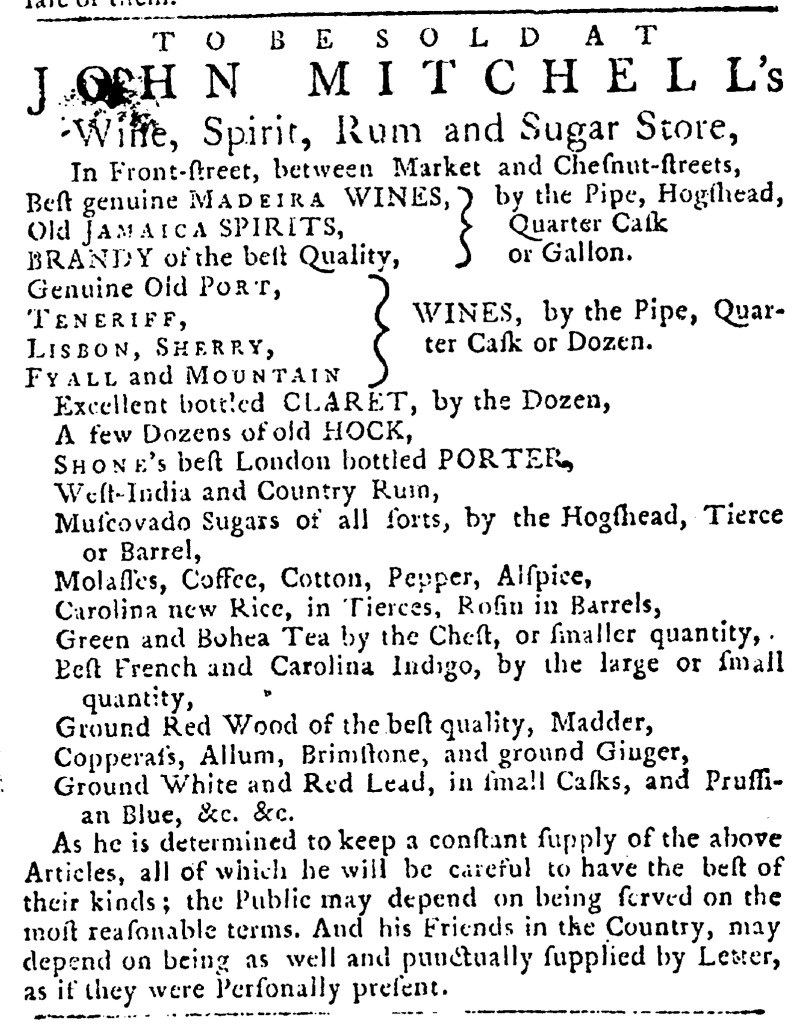

“JOHN MITCHELL’s WINE, SPIRIT, RUM, and SUGAR STORES.”

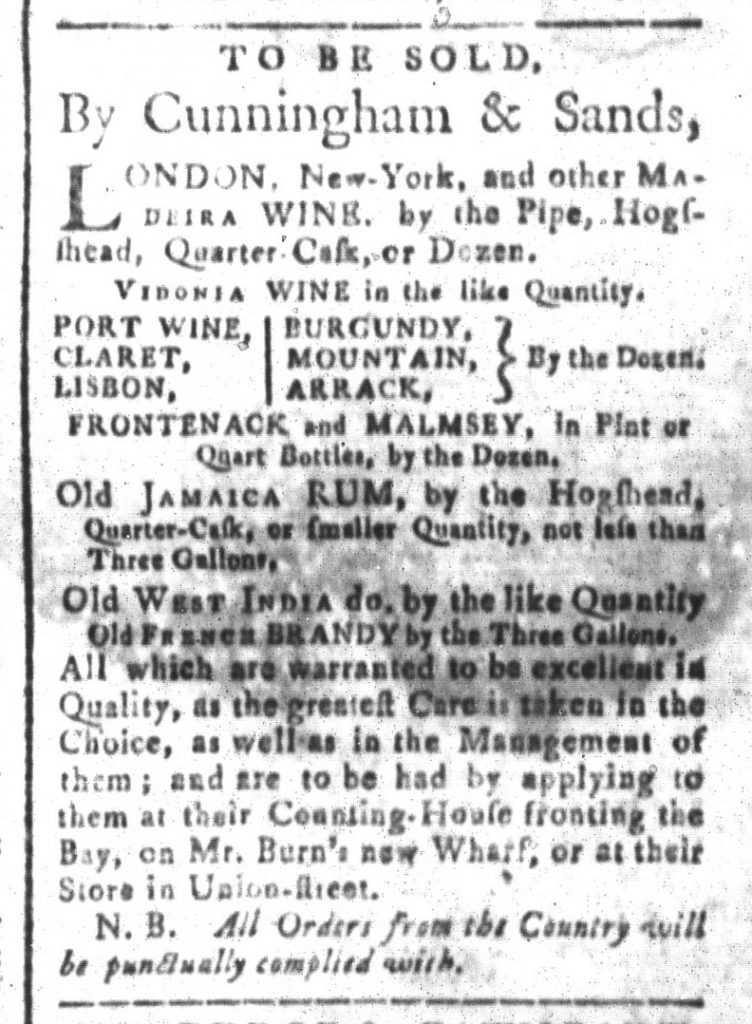

John Mitchell operated an alcohol emporium in Philadelphia in the 1770s. In April 1775, he advertised his “WINE SPIRIT, RUM, and SUGAR STORES” on Front Street, inviting customers in the city and its hinterland to purchase his wares and then retail them at their shops or taverns or enjoy imbibing them at home. To entice prospective customers, he compiled a lengthy list of his current selection along with a pledge to “keep a constant supply of the above Articles” to avoid disappointments associated with selling out of any favorites.

His inventory included, for instance, “BEST Genuine Madeira Wines,” “Excellent bottled Claret,” “Genuine new and old Port Wine,” “Teneriffe and Fyal Wines,” “Red Lisbon Wine,” “Genuine old French Brandy,” “Shone’s, Ben. Kenton and Parker’s best London bottled Porter,” “Genuine Button and Taunton Ale,” and “West-India and New-England Rum,” along with many other choices. For many items, Mitchell listed several sizes, indicating that customers could purchase the right amount for their home or business. He sold Madeira by the gallon or in barrels of various sizes, including “by the pipe, hogshead, [and] quarter-cask.” The bottled porters came “by the hogshead, hamper or dozen” to meet the budget and the convenience of his customers.

The format of Mitchell’s advertisement highlighted the choices. Rather than list his wines and spirits in a dense paragraph, as many advertisers did when they sought to demonstrate the selection of goods they offered to consumers, Mitchell devoted one line to each item. That made it easier for readers to peruse his catalog while also creating visual elements that differentiated his advertisement from news items and other notices that consisted of blocks of text justified on both the left and the right. The variations in white space that resulted from centering each item on its own line made “Best Genuine Madeira Wines,” “Teneriffe and Fyal Wines,” “Genuine old French Brandy,” and “Spanish Brandy” even more visible within the advertisement. Both the extensive accounting of wines and spirits and the design of Mitchell’s notice contributed to attracting the attention of prospective customers.