What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“They now beg the Favour of the different Societies … That they would send the ANTHEMS, usually sung, that they may be inserted.”

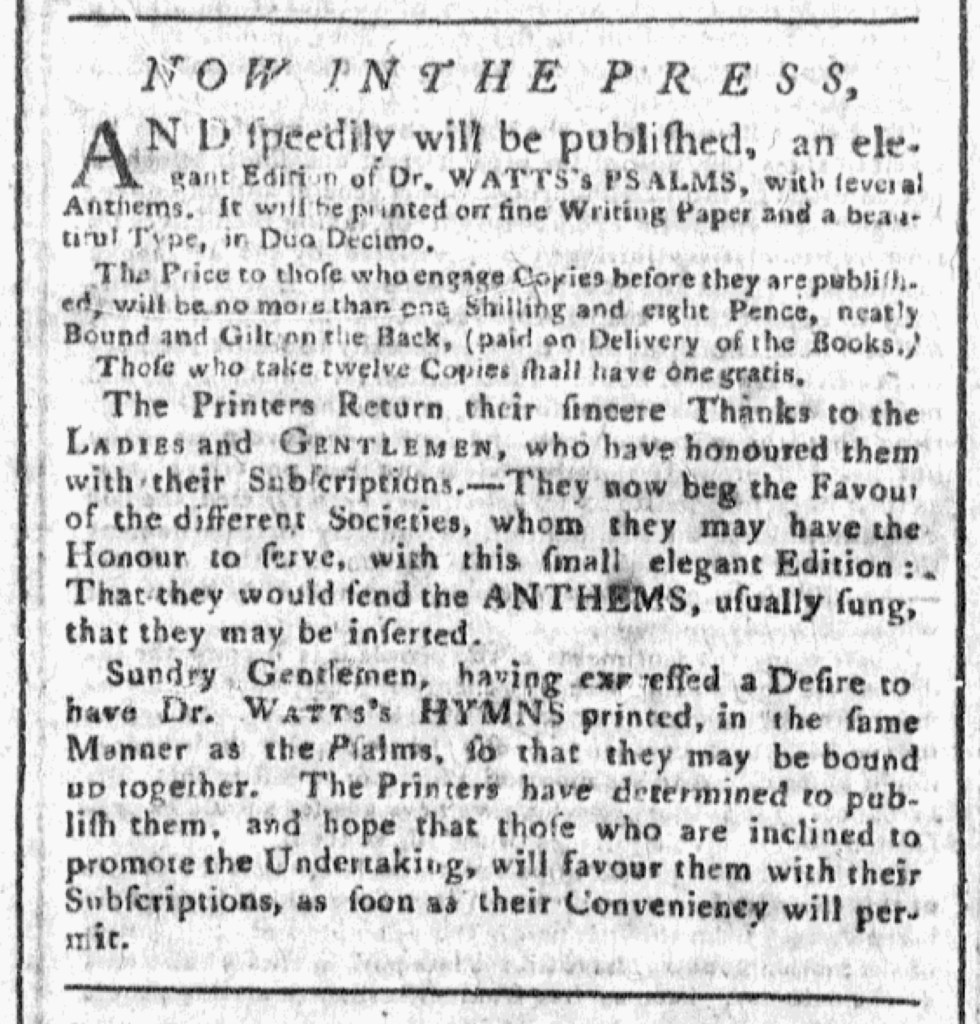

Alexander Robertson, James Robertson, and John Trumull, the printers of the Norwich Packet, placed a notice in their own newspaper to announce that “an Elegant Edition of DR. WATTS’s PSALMS, with several Anthems,” was “NOW IN THE PRESS.” It was not too late for customers to qualify for the bargain price, “no more than one Shilling and eight Pence,” as long as they reserved their copies “before they are published” and offered for sale to the general public. In addition, “Those who take twelve Copies shall have one gratis.” Printers sometimes offered such discounts to retailers who purchased in volume to sell again, though in this case the Robertsons and Trumbull likely had congregations in mind as well.

They certainly attempted to enlist the aid of congregations in submitting additional material to enhance the project and make their edition of Isaac Watts’s translation of The Psalms of David more attractive to prospective customers. The Robertsons and Trumbull “now beg the Favour of the different Societies, whom they may have the Honour to serve, with this small elegant Edition: That they would send the ANTHEMS, usually sung, that they may be inserted.” Such additions would make the books all the more useful to consumers … and marketable for the printers. Having taken the project to press, they aimed to maximize the return on their investment by producing other items that could be bound in a single volume. The book ultimately included eleven anthems, some of them likely contributed by members of the “different Societies” that saw the advertisement in the Norwich Packet.

The Robertsons and Trumbull also envisioned a companion to “Dr. WATTS’s PSALMS.” They reported that “Sundry Gentlemen … expressed a Desire to have Dr. WATTS’s HYMNS printed in the same Manner as the Psalms, so that they may be bound up together.” That does not seem to have happened, at least not in the copy of Watts’s Psalms held by the Library of Congress and reproduced in America’s Historical Imprints. The printers likely did not take that project to press, lacking sufficient demand even though they claimed “Sundry Gentleman” suggested the idea to them. That may have been a ploy to encourage prospective buyers to reserve copies in advance, but when they did not materialize the Robertsons and Trumbull presumably opted not to pursue publishing the hymns.