What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“Advertisements of no more Length than Breadth are inserted for Five Shillings, four Weeks, and One Shilling for each Week after, and larger Advertisements in the same Proportion.”

Some printers kept the colophons for their newspapers quite simple, if they included one at all. The colophon for the Boston-Gazette, for instance, simply stated, “Boston: Printed by EDES & GILL, in Queen-Street, 1773.” The colophon for the Boston Evening-Post was even more streamlined: “BOSTON: Printed by THOMAS & JOHN FLEET.” In each instance, the colophon usually appeared at the bottom of the final column on the last page, rather unobtrusive, though the printers sometimes moved the colophon to the third page if they lacked space.

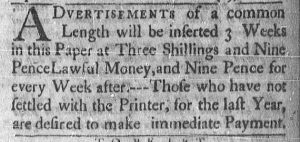

In contrast, other printers inserted much more elaborate colophons that ran across all the columns at the bottom of the final page, that position a permanent element of the design of their newspapers. In such cases, the colophons often doubled as advertisements, providing much more information than the name of the printer and place of publication. Such was the case with the colophon for the New-York Journal. The first line covered the basics: “NEW-YORK: Printed by JOHN HOLT, at the Printing-Office near the COFFEE-HOUSE.” Two more lines made a sales pitch for the services available at Holt’s printing office, declaring “all Sorts of Printing is done in the neatest Manner, with Care and Expedition.” Holt invited job printing orders, whether for broadsides, handbills, trade cards, or blanks, touting both his skill and speed in producing them. He also solicited advertisements for the New-York Journal, an important source of revenue for any newspaper. The colophon even listed the rates for placing notices: “Advertisements of no more Length than Breadth are inserted for Five Shillings, four Weeks, and One Shilling for each Week after, and larger Advertisements in the same Proportion.” That initial fee covered both space in the newspaper, one shilling per week, and setting type, an additional shilling. Setting four weeks as a minimum run generated content while simultaneously enhancing revenues. Many advertisements in the New-York Journal ran for months rather than weeks. (This raises suspicions about whether Holt actually charged for each insertion or continued running some advertisements to testify to current and prospective subscribers and potential advertisers about the popularity of his newspaper.) While every printer welcomed advertisements for their newspapers, most did not regularly comment on the business of advertising. Holt provided important details in his colophon.