What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

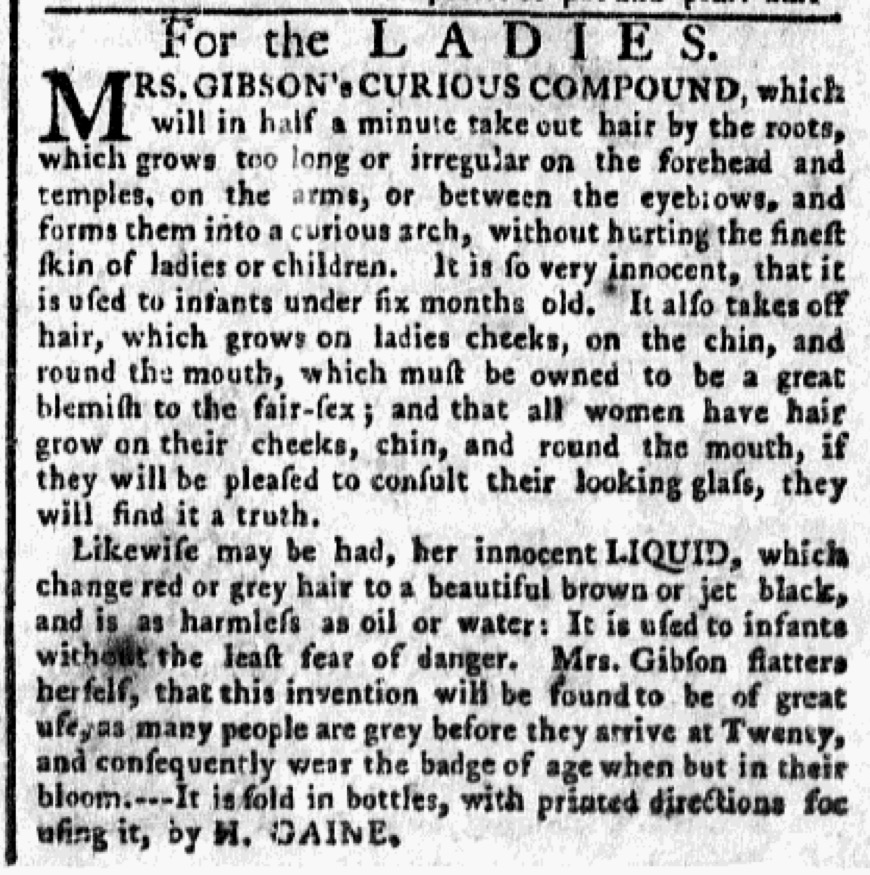

“For the LADIES. MRS. GIBSON’s CURIOUS COMPOUND.”

Cosmetics advertisements occasionally appeared in newspapers during the era of the American Revolution, such as one about “MRS. GIBSON’s CURIOUS COMPOUND” in the July 24, 1775, edition of the New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury. The headline, “For the LADIES,” made clear the target audience. The copy explained that the product “will in half a minute take out hair by the roots, which grows too long or irregular on the forehead and temples, on the arms, or between the eyebrows, and forms them into a curious arch.” Even more appealing, it did so “without hurting the finest skin of ladies or children.” Indeed, Mrs. Gibson’s Curious Compound was so gentle and “so very innocent, that it is used [on] infants under six months old.”

Yet the pitch did not end there. According to the advertisement, the product “also takes off hair, which grows on ladies cheeks, on the chin, and round the mouth, which must be owned to be a great blemish to the fair-sex.” Lest any female readers to feel too confident about their appearance, the advertisement asserted that “all women have hair grow on their cheeks, chin, and round the mouth.” That was not a matter of conjecture but something they could prove with their own eyes: “if they will be pleased to consult their looking glass, they will find it a truth.” The marketing for Mrs. Gibson’s Curious Compound relied on making women feel anxiety about their bodies, not unlike the marketing undertaken by staymakers who addressed “Ladies who are uneasy in their shapes.”

In addition to her hair removal compound, Mrs. Gibson produced an “innocent LIQUID, which change[s] red or grey hair to a beautiful brown or jet black.” Safety once again played a role in promoting the product. The advertisement claimed it was “as harmless as oil or water” and could even be “used [on] infants without the least fear of danger.” The marketing for Mrs. Gibson’s products seemed to have a formula. After a description of the purpose of Mrs. Gibson’s Liquid and a note about safety, the copy attempted to incite feelings of discomfort and self-consciousness among readers. “[T]his invention will be found to be of great use,” the advertisement declared, “as many people are grey before they arrive at Twenty, and consequently wear the badge of age when but in their bloom.” Yet young ladies did not need to appear prematurely old, nor did older ladies need to look their age if they applied Mrs. Gibson’s Liquid to their hair.

Where could women acquire Mrs. Gibson’s Curious Compound and Mrs. Gibson’s Liquid? Hugh Gaine sold both products, along with “printed directions,” at the printing office where he published the New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury. The printer also supplemented his income by marketing Keyser’s Famous Pills once again. Both advertisements appeared in the final column of the first page of his newspaper. Printers often stocked, marketed, and sold patent medicines as an additional revenue stream, but they did not promote cosmetics nearly as often. The printed directions, however, made Mrs. Gibson’s products easy to sell since nobody in the printing office needed to have any direct knowledge of them, just as printed directions made it unnecessary to know much about patent medicines sold in printing offices.