What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

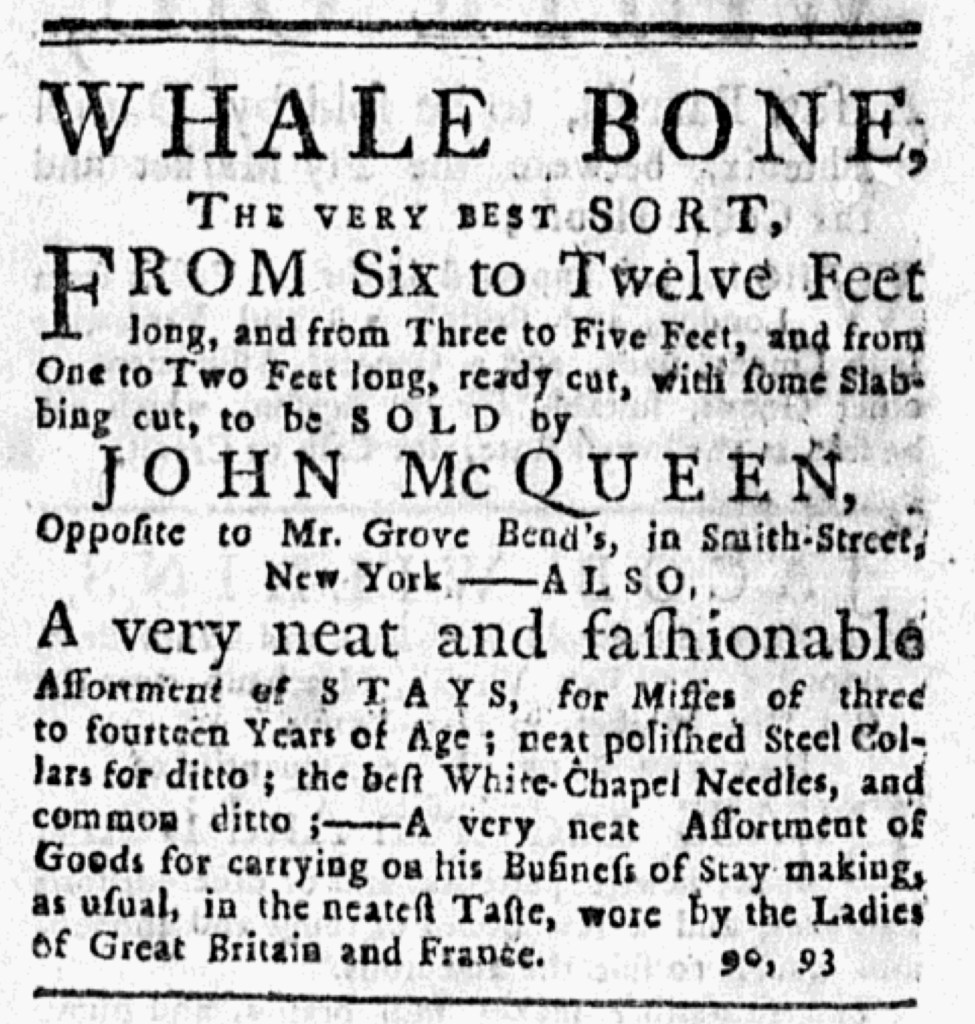

“Carrying on his Business of Stay-making … in the neatest Taste, wore by the Ladies of Great Britain and France.”

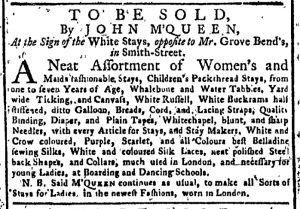

John McQueen continued making and selling stays in New York in 1773. He had been living, working, and advertising in the city for many years. Similar to a corset, a pair of stays, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, consisted of a “laced underbodice, stiffened by the insertion of whale-bone (sometimes of metal or wood) worn by women (sometimes by men) to give shape and support to the figure.” Furthermore, the “use of the plural is due to the fact that stays were originally (as they still are usually) made in two pieces laced together.” John White included a woodcut depicting a pair of stays and lacing in his advertisement in the September 19, 1772, edition of the Pennsylvania Chronicle.

When he advertised in the New-York Journal in June 1773, McQueen emphasized his role as a supplier of “WHALE BONE” of “THE VERY BEST SORT” to other staymakers. In addition, he stocked a “very neat and fashionable Assortment of STAYS, for Misses of three to fourteen Years of Age.” Apparently, both staymakers and consumers did not believe that girls were ever too young to deploy these devices to shape their figures.” Richard Norris, another staymaker in New York, regularly placed newspaper advertisements addressed to “young Ladies and growing Misses” as well as “Any Ladies uneasy in their shapes.” Cultivating and preying on such anxieties was not invented by the modern beauty and fashion industries.

McQueen also resorted to another familiar refrain, declaring that he had on hand a “very neat Assortment of Goods for carrying on his Business of Stay-making, as usual, in the neatest Taste, wore by the Ladies of Great Britain and France.” He often made such transatlantic connections, suggesting to prospective customers that he could assist them in demonstrating the sort of sophistication associated with cosmopolitan cities in Europe. In 1766, he declared that he made stays “in the newest Fashion that is wore by the Ladies of Great-Britain or France.” In another advertisement from 1767, he confided that he made “all sorts of Stays for Ladies, in the newest Fashions that is wore in London.” Encouraging anxiety about the female form and making comparisons to fashionable elites became standard marketing strategies for McQueen and other staymakers in the eighteenth century.