What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

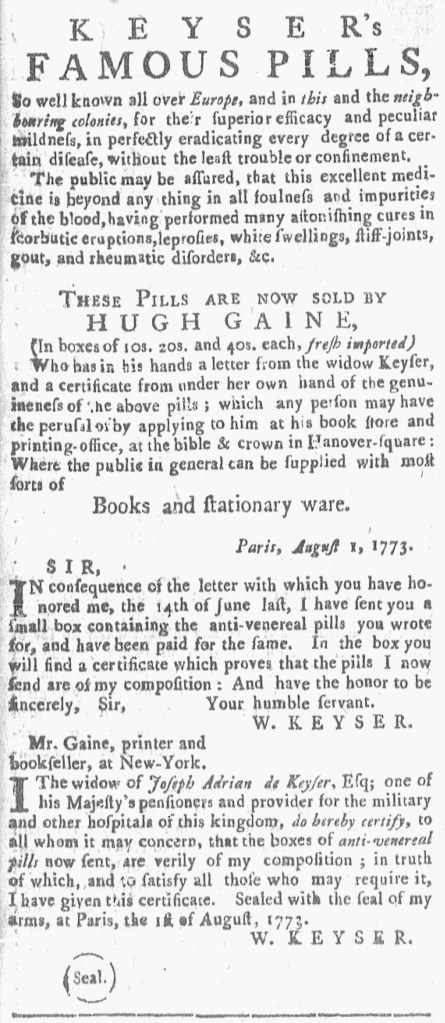

“☛K ☛E ☛Y ☛S ☛E ☛R’s Famous Pills.”

Hugh Gaine, “PRINTER, BOOKSELLER, and STATIONER” (as he described himself in the masthead of the New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury), continued marketing “KEYSER’s Famous Pills,” a remedy for syphilis, in the February 21, 1774, edition of his newspaper. He gave his advertisement a privileged place. It was the first item in the first column on the first page, making it difficult for readers to miss. The advertisement consisted of several portions, collectively extending half a column. The first two portions, enclosed within a border composed of decorative type, provided a description of the efficacy of the pills in “eradicating every Degree of a certain DISEASE” and curing other maladies and offered an overview of “a Letter from the Widow Keyser, and a Certificate from under her own Hand” testifying to the “Genuineness” of the pills Gaine sold. In recent months, both apothecaries and printers in New York and Philadelphia engaged in public disputes about who stocked authentic pills and who peddled counterfeits. Even though Gaine invited the public to examine the letter and certificate at his store in Hanover Square (where they could shop for “Books and Stationary Ware”), the final two portions of his advertisement consisted of transcriptions of those items and a representation of the widow’s “Seal of my Arms.”

The decorative border, the only one in that issue of the New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, made Gaine’s advertisement more visible among the contents of the newspaper, yet that was not his only innovative use of graphic design. For several weeks he had been playing with manicules as a means of drawing attention to his advertisements. In this instance, a manicule appeared before each letter of “KEYSER,” pointing to the right. Such had been the case when the advertisement ran on January 24 and 31 and February 7 and 14. The first time he incorporated manicules into his advertisement for “KEYSER’s FAMOUS PILLS,” however, he had twelve pairs pointing at each other, six pairs above the name of the product and six pairs below the name of the product. That version appeared just once, on November 1, 1773. Subsequently, Gaine positioned manicules above each letter of “KEYSER,” pointing down, in six issues. That arrangement ran on November 8, 15, and 22 and December 6 and 13, each time with a border. When Gaine used it again on January 17, 1774, he did not include a border but once again had six manicules pointing down, one above each letter of “KEYSER.” He apparently did not expect the appeals in his advertisements to do all the work of marketing the patent medicine. Instead, Gaine believed that graphic design aided his efforts to reach prospective customers who much preferred fingers literally pointing at the name of the pills in advertisements over fingers figuratively pointing at them by others who suspected them of being afflicted with “a certain DISEASE.”

**********