What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

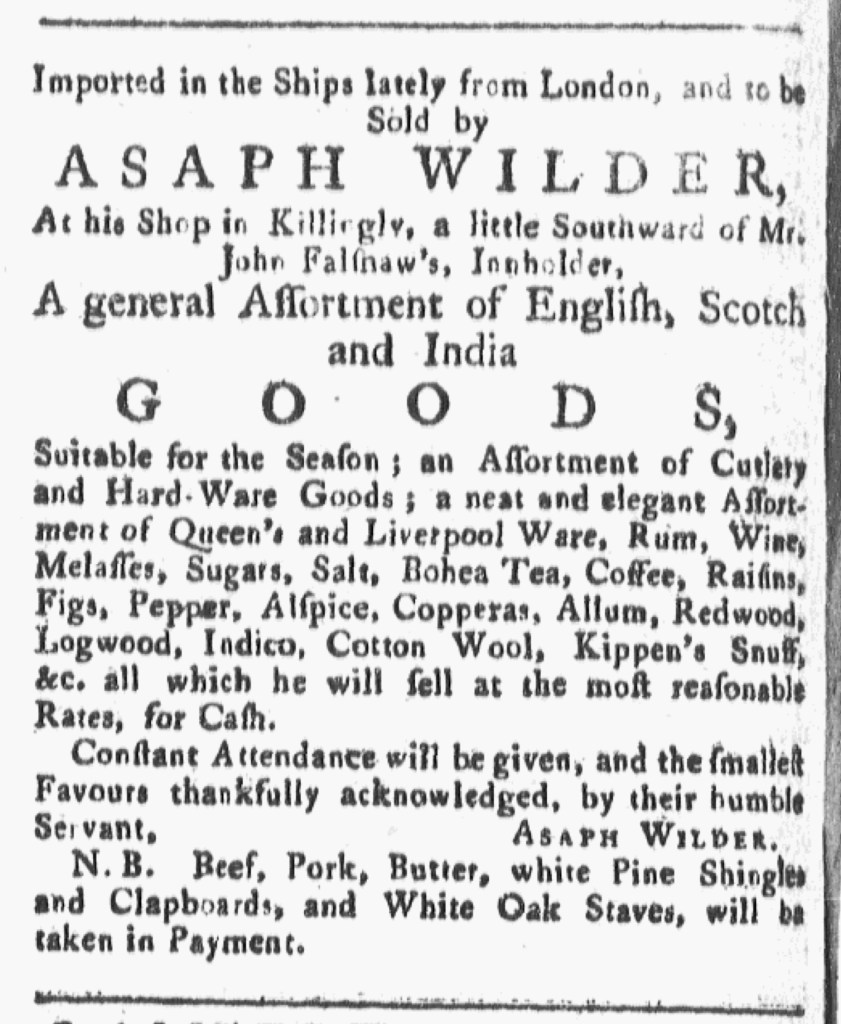

“At his Shop in Killingly.”

In the early 1770s, the Providence Gazette served readers … and advertisers … in Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Massachusetts. At the time that Asaph Wilder published his advertisement for a “general Assortment of English, Scotch and India GOODS” available at his shop in Killingly, Connecticut, about twenty-five miles west of Providence, printers published only three newspapers in his colony, the Connecticut Courant in Hartford, the New-London Gazette, and the Connecticut Journal and New-Haven Post-Boy. In Massachusetts, five printing offices in Boston and one in Salem printed newspapers, but none to the west or south. In Rhode Island, John Carter published the Providence Gazette and Solomon Southwick published the Newport Mercury. That made the Providence Gazette the local newspaper for colonizers like Wilder in Killingly as well as others in towns in all three colonies.

Though Wilder kept shop in the countryside, he wanted prospective customers to know that he maintained an inventory that rivaled what they would find in Providence. His “general Assortment” included “an Assortment of Cutlery and Hard-Ware Goods” and “a neat and elegant Assortment of Queen’s and Liverpool Ware” as well as coffee, tea, and several grocery items. Rather than leftovers, his inventory consisted of goods “Suitable for the Season” that arrived in the colonies via “the Ships lately from London.” Yet customers in Killingly and nearby towns did not have to pay a premium for the convenience of acquiring these items at Wilder’s shop rather than sending away for them or making a trip to Providence or another port. The shopkeeper pledged that he “will sell at the most reasonable Rates,” either in cash or in exchange for commodities like “Beef, Pork, Butter, white Pine Shingles and Clapboards, and White Oak Staves.” Wilder offered consumers in the countryside the same sorts of goods available to their counterparts in larger towns and cities, but made accommodations for payment tied to the local economy. Even if some prospective customers suspected that Wilder’s selection was not as extensive as he suggested, his willingness to deal with them on such terms may have been a factor in winning their business.