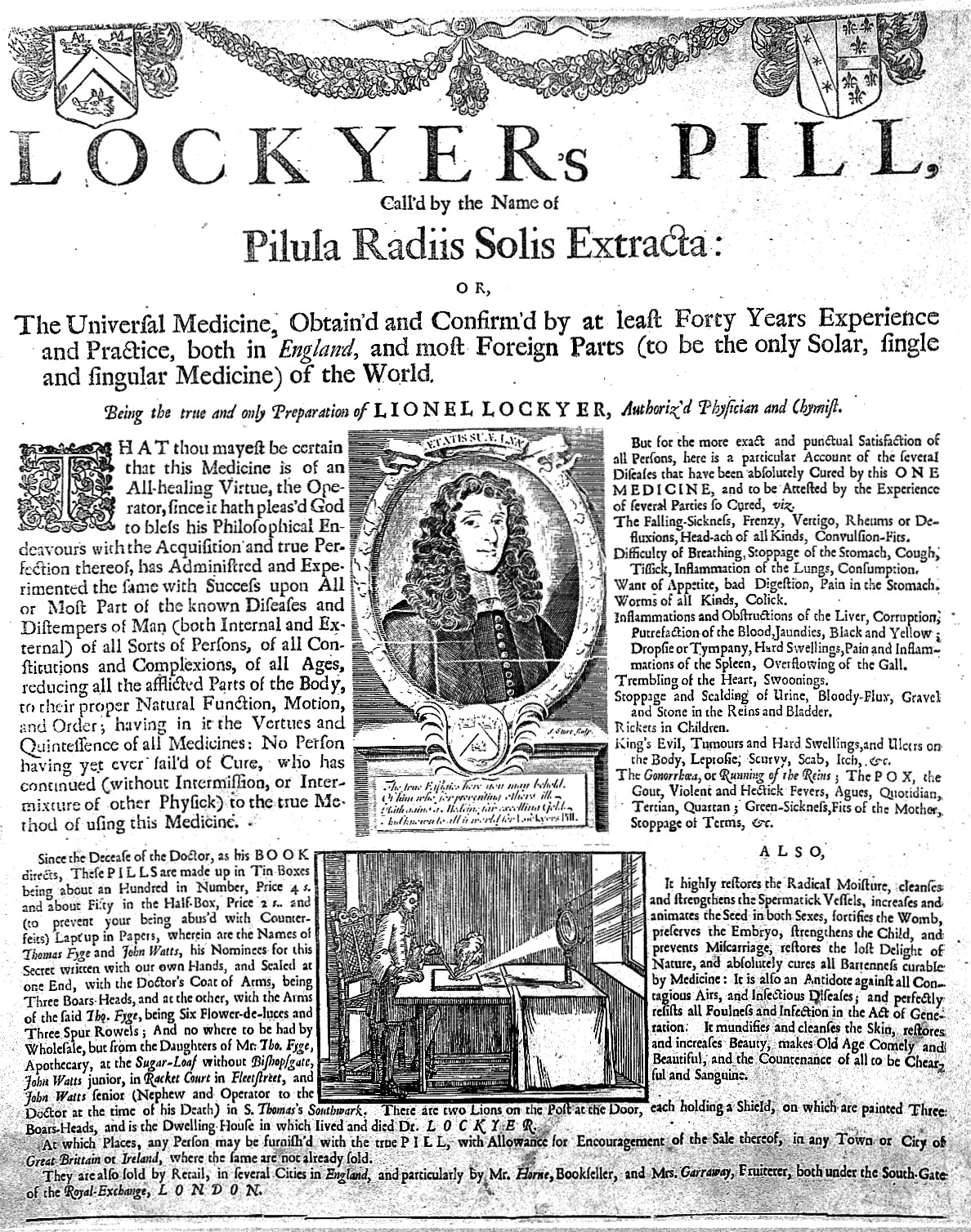

Being able to participate in the Adverts 250 Project was a truly eye-opening experience. This project not only provided a window into a week in colonial America, but also a look into what many historians do every day. Arguably the most interesting part of the project was getting a glimpse at day-to-day life in the colonies. I learned a lot not only from the advertisements I selected, but also in just scouring through the newspapers. It was through these newspapers I was able to get the sense what it was like to be a colonist.: seeing what goods were commonly for sale, realizing which goods were readily available or were not as regularly imported, and even seeing what was considered newsworthy. Items such as clothing and textiles were included in nearly every advertisement I saw, yet others were more specific and offered hardware, tools, or medicines.

This was my third opportunity to partake in a community service or digital humanities project in which the process was not that of a standard history course. Hoping to find my way into a career as an historian, it is refreshing to look at the profession in new ways, specifically using the digital humanities to research nearly any historical topic imaginable, and getting to look at firsthand accounts from that specific period. As the project moved closer and closer, it was intimidating for sure, as finding advertisements from 250 ago seemed like an extremely tall task. However, being able to access the immense collection of authentic historical materials using the American Antiquarian Society as well as the Early American Newspapers database was a real treat. Each of these facilitated nearly every aspect of this project.

Despite the American Antiquarian Society and online databases making the hunt for advertisements dramatically easier, by far the most difficult part for me was writing the blog posts. It was clear after my first drafts of the first three days that I had never written a blog before. Every one of my drafts was all over the place, and basically just a summary of what the advertisement contained without any additional analysis. Writing a blog is much different than writing an essay, I’ve learned. I really had to work to eliminate passive voice, as well as speak in the first person when appropriate. To improve my first drafts I worked with Prof. Keyes to focus on one aspect of each advertisement that was especially significant and stood out. I then added in my own thoughts and opinions and was able to find my voice.

The blogs were fairly short but the tweets even shorter, and being able to compress a lengthy advertisement down into 140 characters was tricky as well. Each advertisement contained so many goods that whenever I omitted something I was concerned that I had left out a significant part. Using Twitter to expand the audience of the project was intriguing because social media is one of the best ways available in today’s society to spread the word and engage others. Seeing other historians “liking” and “re-tweeting” posts related to this project was awesome, as it showed that the work I was putting in was being seen and read by more people than I had expected. It showed that people are truly interested in the project, and that reinforcement, though miniscule, shows me that my work had a purpose, which makes all of the hard work worth it.