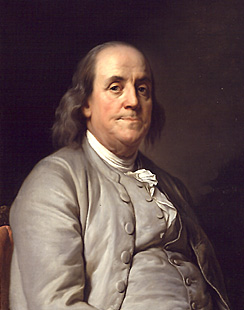

Today is an important day for specialists in early American print culture, for Benjamin Franklin was born on January 17, 1706 (January 6, 1705, Old Style), in Boston. Among his many other accomplishments, Franklin is known as the “Father of American Advertising.” Although I have argued elsewhere that this title should more accurately be bestowed upon Mathew Carey (in my view more prolific and innovative in the realm of advertising as a printer, publisher, and advocate of marketing), I recognize that Franklin deserves credit as well. Franklin is often known as “The First American,” so it not surprising that others should rank him first among the founders of advertising in America.

Franklin purchased the Pennsylvania Gazette in 1729. In the wake of becoming printer, he experimented with the visual layout of advertisements that appeared in the weekly newspaper, incorporating significantly more white space and varying font sizes in order to better attract readers’ and potential customers’ attention. Advertising flourished in the Pennsylvania Gazette, which expanded from two to four pages in part to accommodate the greater number of commercial notices.

Many historians of the press and print culture in early America have noted that Franklin became wealthy and retired as a printer in favor of a multitude of other pursuits in part because of the revenue he collected from advertising. Others, especially David Waldstreicher, have underscored that this wealth was amassed through participation in the colonial slave trade. The advertisements for goods and services featured in the Pennsylvania Gazette included announcements about buying and selling enslaved men, women, and children as well as notices offering rewards for those who escaped from bondage.

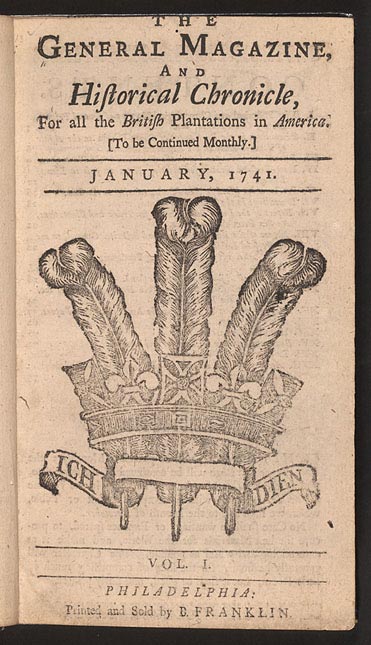

In 1741 Franklin published one of colonial America’s first magazines, The General Magazine and Historical Chronicle, for all the British Plantations in America (which barely missed out on being the first American magazine, a distinction earned by Franklin’s competitor, Andrew Bradford, with The American Magazine or Monthly View of the Political State of the British Colonies). The magazine lasted only a handful of issues, but that was sufficient for Franklin to become the first American printer to include an advertisement in a magazine (though advertising did not become a standard part of magazine publication until special advertising wrappers were developed later in the century — and Mathew Carey was unarguably the master of that medium).

In 1744 Franklin published an octavo-sized Catalogue of Choice and Valuable Books, including 445 entries. This is the first known American book catalogue aimed at consumers (though the Library Company of Philadelphia previously published catalogs listing their holdings in 1733, 1735, and 1741). Later that same year, Franklin printed a Catalogue of Books to Be Sold at Auction.

Franklin pursued advertising through many media in eighteenth-century America, earning recognition as one of the founders of American advertising. Happy 318th birthday, Benjamin Franklin!