What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“I Acknowledge that I have at several times spoken in favour of the laws of Taxation.”

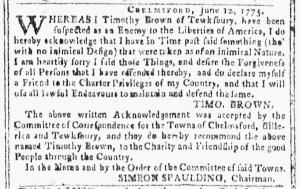

Lemuel Bower wanted to return to the good graces of his community in the fall of 1775. Events that occurred since the previous April – the battles at Lexington and Concord, the siege of Boston, the Battle of Bunker Hill, the Second Continental Congress appointing George Washington as commander in chief of the Continental Army, an American invasion of Quebec – had intensified feelings about the imperial crisis and, apparently, made for a difficult situation for Bower since he had expressed Tory sentiments in the past. In hopes of moving beyond that, he composed a statement that appeared in the October 12, 1775, edition of the New-York Journal.

“I Acknowledge,” Bower confessed, “I have at several times spoken in favour of the laws of Taxation, and against the measures pursued by America to procure Redress, and have thereby justly merited the displeasure of my country.” To remedy that, “I beg forgiveness, and so solemnly promise to submit to the rules of the Continental and Provincial Congresses,” including abiding by the nonimportation and nonconsumption provisions in the Continental Association. Furthermore, Bower pledged, “I never will speak or act in opposition to their order, but will conduct according to their directions, to the utmost of my power.” He did not state that he had a change of heart, only that he would quietly act as supporters of the American cause were supposed to act rather than engage in vocal opposition. As William Huntting Howell has argued, such compliance, especially when expressed in a public forum, may have been more important to most Patriots than whether Bower truly agreed with them.[1] How he acted and what he said was more important than what he believed as long as he kept his thoughts to himself.

Bower did indeed express his regrets and his promise to behave better in a public forum. He concluded his statement with a note that “this I desire should be published in the public prints. When it appeared in the New-York Journal, it ran immediately below a notice from the Committee of Inspection and Observation in Stanford, New York, that labeled two Loyalists as “enemies to the liberties of their country” and instructed the public “to break off all commerce, dealings and connections with them.” That was the treatment that Bower sought to avoid! That notice appeared immediately below news from throughout the colony. Bower’s statement ran immediately above paid advertisements. The two statements concerning the political principles of colonizers thus served as a transition from news to advertising in that issue of the New-York Journal. Did John Holt, the printer, treat them as paid notices? Did he require Bower to pay to insert his statement? Or did the Patriot printer publish one or both gratis? Perhaps he printed the statement from the Committee of Inspection and Observation for free but made Bower pay to publish his penance. Whatever the case, Bower’s statement was not clearly a news item nor an advertisement but could have been considered both simultaneously by eighteenth-century readers.

**********

[1] William Huntting Howell, “Entering the Lists: The Politics of Ephemera in Eastern Massachusetts, 1774,” Early American Studies 9, no. 1 (Winter 2011): 187-217.