What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

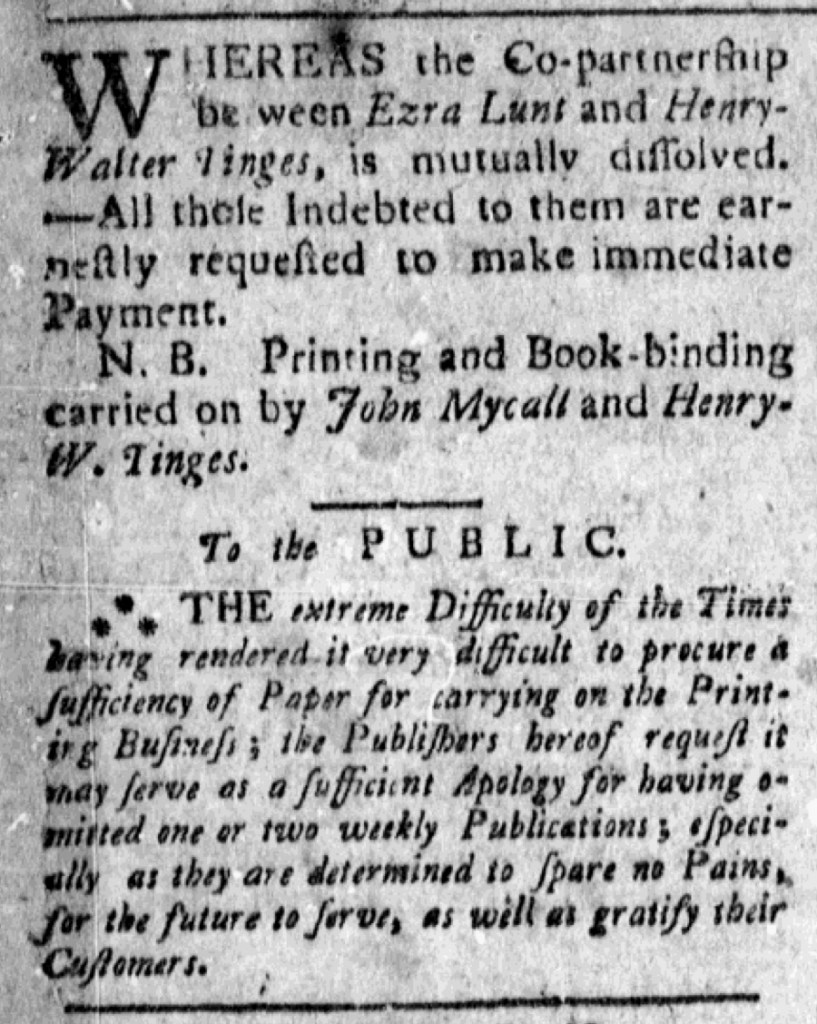

“THE extreme Difficulty of the Times having rendered it very difficult to procure a sufficiency of Paper.”

A notice on the first page of the July 22, 1775, edition of the Essex Journal, Or, the Massachusetts and New-Hampshire General Advertiser informed readers that the “Co-partnership between Ezra Lunt and Henry-Walter Tinges,” the publishers of the newspaper, “is mutually dissolved” and called on “those Indebted to them” to settle accounts. Yet the printing office in Newburyport was not being shuttered. Instead, a nota bene declared, “Printing and Book-binding carried on by John Mycall and Henry-W. Tinges.” Mycall became Tinges’s third partner in less than three years. The young printer first went into business with Isaiah Thomas, the printer of the Massachusetts Spy in the late fall of 1773. The more experienced printer remained in Boston while his junior partner oversaw the printing office and their new newspaper. The partnership lasted less than a year. On August 17, 1774, they notified the public that they “mutually dissolved” their partnership, but the “Printing Business is carried on as usual, by Ezra Lunt and Henry W. Tinges.”

Nearly a year later, Lunt departed and Mycall took his place. As their first order of business, the new partners addressed some of the challenges the newspaper faced since the battles at Lexington and Concord three months earlier. “THE extreme Difficulty of the Times having rendered it very difficult to procure a sufficiency of Paper for carrying on the Printing Business,” they lamented, “the Publishers hereof request it may serve as a sufficient Apology for having immitted one or two weekly Publications.” Indeed, publication had been sporadic during May, immediately after the outbreak of hostilities, returned to a regular schedule in June, and then missed a week in July before announcing the departure of Lunt and arrival of Mycall. The Essex Journal had missed only two issues, but the publishers did not consistently distribute the newspapers on the same day each week. That likely added to the impression that they had not supplied all the newspapers that their customers expected. In addition, the two most recent issues, June 30 and July, and the one that carried the notice about the new partnership consisted of only two pages rather than the usual four. Mycall and Tinges vowed that “they are determined to spare no Pains, for the future to serve, as well as gratify their Customers.” Mycall and Tinges kept that promise. Publication returned to a regular schedule with only minor disruptions.