What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Lessening the unnecessary Importation of such Articles as may be fabricated among ourselves.”

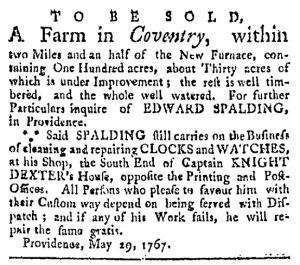

Edward Spalding (sometimes Spauldin), a clockmaker, placed advertisements in the Providence Gazette fairly frequently in the late 1760s. In fact, he ran a notice for four weeks in August 1766 when the newspaper resumed publication after the repeal of the Stamp Act and the printer resolved other concerns related to the business. He had also inserted a notice in one of the few “extraordinary” issues that appeared while the Stamp Act was still in effect.

Although Spalding sometimes recycled material from one advertisement to the next, at other times he submitted completely new copy that addressed current political and commercial issues, attempting to leverage them to the benefit of his business. In June 1768, for instance, he linked the clocks and watches made and sold in his shop with efforts to achieve greater self-sufficiency throughout the colonies as a means of resisting the Townshend Act and other abuses by Parliament. To that end, he opened his advertisement by announcing two recent additions to his workshop. First, he had “just supplied himself with a compleat Sett of Tools.” He also “engaged a Master Workman” to contribute both skill and labor. As a result, Spalding advised potential customers that he was particularly prepared “to carry on his Business in a very extensive Manner.”

Artisans often invoked that standardized phrase when making appeals about their skill and the quality of the items produced in their workshop, but Spalding did not conclude his pitch to potential patrons there. Instead, he mobilized that common appeal by explaining to prospective customers that since he produced clocks and watches of such high quality – in part thanks to the new tools and “Master Workman” – that they did not need to purchase alternatives made in Britain only because they assumed imported clocks and watches were superior in construction. Spalding took on the expenses of new tools and a new workman in his shop “to contribute his Mite towards lessening the unnecessary Importation of such Articles as may be fabricated among ourselves.” That appeal certainly resonated with ongoing conversation about domestic production that appeared elsewhere in colonial newspapers in 1768.

Ultimately, Spalding placed the responsibility on consumers: “To this Undertaking he flatters himself the Public will afford all die Encouragement.” It did not matter if leaders advocated in favor of “local manufactures” and artisans heeded the call if colonists did not choose to purchase those products. Spalding wished to earn a living; the imperial crisis presented a new opportunity for convincing customers that they had not a choice but instead an obligation to support his business.