What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

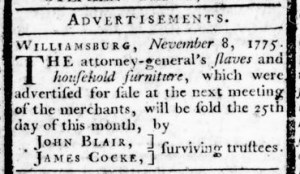

“JOHN BLAIR, JAMES COCKE, surviving trustees.”

An advertisement about the upcoming sale of the “attorney-general’s slaves and household furniture” in the November 10, 1775, edition of Alexander Purdie’s Virginia Gazette was signed by John Blair and James Cocke, the “surviving trustees.” Upon learning of the death of Peyton Randolph, one of the original trustees, they had updated an advertisement that had been running in that newspaper as well as John Pinkney’s Virginia Gazette and John Dixon and William Hunter’s Virginia Gazette for several weeks. John Randolph, the King’s Attorney General for the colony and a loyalist, had departed for England, leaving his brother, Peyton, along with Blair and Cocke as trustees to oversee and sell his estate. Peyton, a patriot and the president of the First Continental Congress, was in Philadelphia representing Virginia in the Second Continental Congress when he unexpectedly died, leaving Blair and Cocke as the “surviving trustees.”

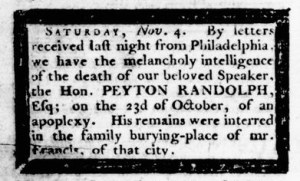

Among the printers in Williamsburg, Purdie published the news of Randolph’s death first, nearly a week ahead of the other two newspapers. Given that each published a new issue once a week, the news spread ahead of it appearing in print. All the same, Purdie supplemented the brief notice that he ran in the November 3 edition with extensive coverage in the next issue on November 10. “LAST sunday died of an apoplectick stroke,” the report began, “the hon. PEYTON RANDOLPH, Esq; of Virginia, late President of the Continental Congress, and Speaker of the House of Burgesses of that colony.” On the following Tuesday, “his remains were removed … to Christ church, where an excellent sermon on the mournful occasion was preached … after which the corpse was carried to the burial ground, and deposited in a vault until it can be conveyed to Virginia.” The dignitaries in the funeral procession included John Hancock, then serving as president of the Second Continental Congress, other “members of the Congress,” members of the Pennsylvania Assembly, and the mayor of Philadelphia. Elsewhere in that issue, Purdie printed a memorial to Randolph, an eighteenth-century version of an obituary. He also inserted a notice from Williamsburg’s Masonic Lodge: “Ordered, THAT the members of this Lodge go into mourning, for six weeks, for the late honourable and worthy provincial grand master, Peyton Randolph, esquire.” To honor Randolph, Purdie enclosed the contents of the entire issue within thick black borders that signaled mourning. Those borders ran on either side of the updated advertisement placed by the “surviving trustees” of John Randolph’s estate.