What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Subscribers Names may be annexed to the Work.”

When John Carter, the printer of the Providence Gazette, set about publishing a new edition of English Liberties, Or the Free-Born Subject’s Inheritance: Containing Magna Charta, Charta de Foresta, the Statute de Tallagio non Concedendo, the Habeas Corpus Act, and Several Other Statutes, with Comments on Each of Them, he started with subscription proposals. Early American printers often did not take books directly to press. Instead, they disseminated proposals that described their intended projects, simultaneously seeking to gauge the market and to incite demand. In requesting that subscribers reserve their copies in advance, sometimes asking them to pay a deposit, printers determined whether publishing proposed books would be viable ventures and, if so, how many copies to print to avoid producing surplus copies that cut into profits. Subscription proposals ran as advertisements in newspapers and, for some proposed works, “Subscription-Papers” circulated separately as handbills, broadsides, and pamphlets.

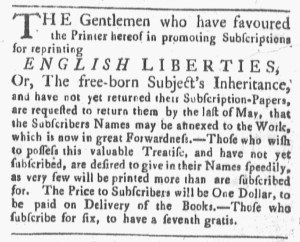

Many printers recruited local agents to assist them in collecting the names of subscribers and how many copies each wished to reserve. Carter did so with English Liberties. In an update in the April 23, 1774, edition of the Providence Gazette, he advised that the book “is now in great Forwardness.” Most likely much of the type had been set and supplies, such as paper, acquired by the printing office. Carter instructed the “Gentlemen who have favoured the Printer hereof in promoting Subscriptions … to return [their subscription papers] by the last of May.” He needed to receive them by that time so “the Subscribers Names may be annexed to the Work.” That was a popular strategy for inciting demand among prospective customers, promising that their names would appear along with others who also subscribed. They became part of a community of readers, even if they never met, and, in this instance, a community of citizens committed to those “ENGLISH LIBERTIES” that had been “The free-born Subject’s Inheritance” for generations. Printers suggested to those who had not yet subscribed that they needed to do so if they wished to be recognized alongside their friends and acquaintances and the most prominent members of their communities who already made a statement about the causes that they supported by subscribing for one or more copies.

Carter deployed other marketing strategies to encourage subscriptions for English Liberties. He warned that “very few will be printed more than are subscribed for,” so anyone who even had an inkling that they might want a copy should not depend on waiting to purchase the book after it went to press. In addition, Carter offered a premium: “Those who subscribe for six, to have a seventh gratis.” Subscribers who purchased multiple copies would receive a free one as a reward.

Carter did indeed insert a list of “SUBSCRIBERS NAMES” at the end of the book. They appeared in somewhat alphabetical order, with last names starting with “A” coming first, followed by “B,” and so on. Carter indicated the town for subscribers who did not reside in Providence and, within each letter, clustered subscribers from the same town together. That made it easier for subscribers to determine which of their neighbors had joined them in supporting the enterprise. Most were from towns in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Connecticut, but some subscribed from greater distances, including Robert Johnston of Chester County in Pennsylvania and Thomas Tillyer in Philadelphia. The roster of subscribers included nearly five hundred names, mostly men, but also Mrs. Elizabeth Belvher of Wrentham, Massachusetts, several lawyers and ministers, and even Darius Sessions, the deputy governor of Rhode Island. For those who subscribed for multiple copies, Carter listed how many. A few purchased two or three copies, but more commonly subscribers purchased six, a sign of the effectiveness of the printer’s marketing strategy.

Not all subscription proposals resulted in publishing books. Printers sometimes learned that they could not generate sufficient demand. In this case, however, the combination of the subject matter’s relationship to the political climate, widespread distribution of subscription papers to local agents, publishing the names of subscribers, and free copies for those who purchased at least six contributed to the success of the venture, though it had taken more than a year.