What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“Iron utensils, so much recommended by physicians for their safety.”

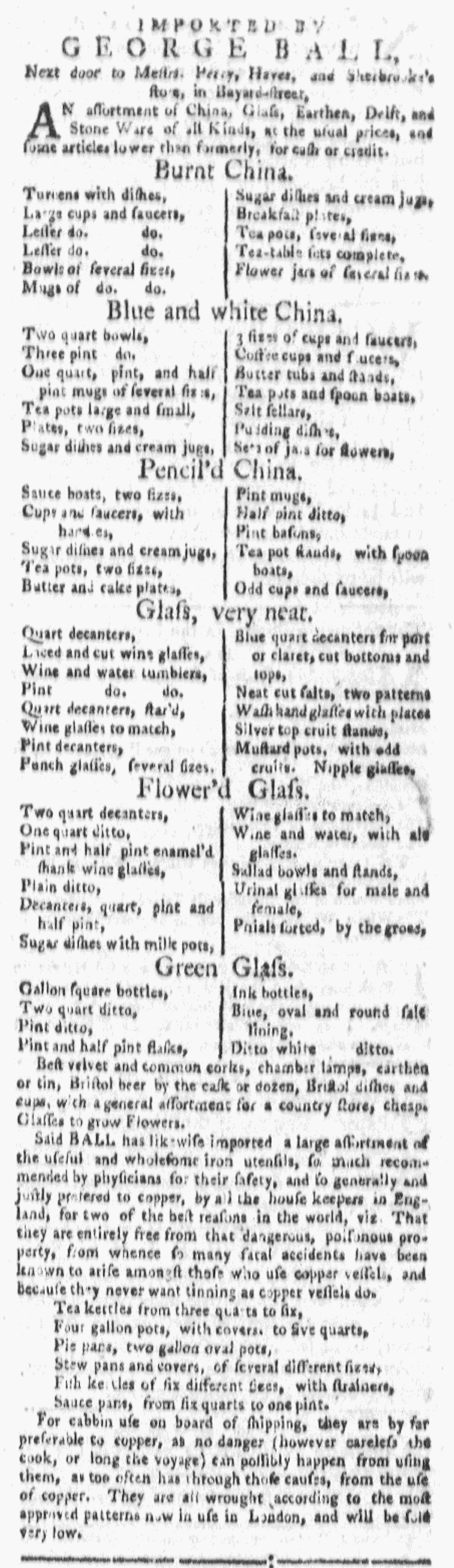

As July 1775 came to a close, George Ball advertised an “assortment of China, Glass, Earthen, Delft, and Stone Ware of all Kinds” in Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer. He conveniently did not mention when he acquired his merchandise, whether it arrived in the colonies before the Continental Association went into effect, though the headline did proclaim “IMPORTED BY GEORGE BALL” rather than “JUST IMPORTED BY GEORGE BALL.”

Most of Ball’s advertisement consisted of a list of the various items he stocked, divided into categories that included “Burnt China,” “Blue and white China,” “Pencil’d China,” “Glass, very neat,” “Flower’d Glass,” and “Green Glass.” In the final third of the advertisement, however, Ball highlighted “iron utensils” and made a pitch to convince consumers to demand iron tea kettles, iron pots, iron saucepans, iron pie pans, and iron stew pans with iron covers instead of copper ones. Those “useful and wholesome iron utensils,” Ball asserted, were “so much recommended by physicians for their safety” and, accordingly, “so generally and justly prefered to copper, by all the house keepers in England.” Ball made health and safety the centerpiece of his marketing, citing “the best reasons in the world.” He emphasized that cookware made of iron was “entirely free from that dangerous, poisonous property, from whence so many fatal accidents have been known to arise amongst those who use copper vessels.” As a bonus, consumers could save money over time since “iron utensils” did not need the same maintenance: “they never want tinning as copper vessels do.” In addition to the “house keepers” of New York, Ball promoted his wares to readers responsible for outfitting ships. “For cabbin use on board shipping,” he declared, iron items “are by far preferable to copper, as no danger (however careless the cook, or long the voyage) can possibly happen from using them, as too often has through those causes, from the use of copper.” Ball concluded by noting that his “iron utensils” were “all wrought according to the most approved patterns now in use in London,” but that nod to fashion and taste merely supplemented his primary marketing strategy. For consumers concerned about health and safety in the kitchen, he carried the cookware that they needed to use instead of taking chances with copper kettles, pots, and pans.