What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“And many more articles, too tedious to insert.”

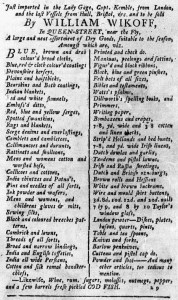

William Wikoff sold a variety of imported goods at his store in Hanover Square in New York in the early 1770s. In an advertisement in the February 11, 1773, edition of the New-York Journal, for instance, he informed consumers that he stocked “a very handsome Assortment of Dry Goods, suitable for the Season,” and then offered a short catalog of some of those items to demonstrate the array of choices. Wikoff listed a variety of textiles, including a “beautiful assortment of callicoes and cottons,” as well as “Mens and womens white and beaver gloves of the best kind” and “Childrens yellow and red leather shoes.” Beyond fabrics and garments, Wikoff also had “Taylors thimbles,” “spelling books,” “knives and forks,” and “Bed furniture.”

To help readers navigate his advertisement, Wikoff opted for two columns with two or three items on each line. That made it easier to read than advertisements that amalgamated everything together into a dense paragraph of text. The merchant apparently considered that format effective, having used it on another occasion. He also incorporated another element from his previous advertisements, asserting that that the list of merchandise did not cover everything available at his shop. Wikoff confided that he carried “many more articles, too tedious to insert,” echoing his assertion in another advertisement that he sold “many other articles, too tedious to mention.” Prospective customers, he suggested, would have a much more enjoyable experience browsing at his store than reading through a lengthy catalog in the newspaper.

That strategy allowed him to entice prospective customers who were curious about what else they might encounter at his store. At the same time, Wikoff limited his advertising expenses. He could have published an even longer list, but that would have cost more. He likely aimed for what he considered the right balance between showcasing a good portion of the selection at his store and how much he was willing to spend on the advertisement. In doing so, he offered enough details to capture readers’ attention and demonstrated that they were likely to find an even greater variety when they shopped at his store.