What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“All kinds of Windsor Chairs.”

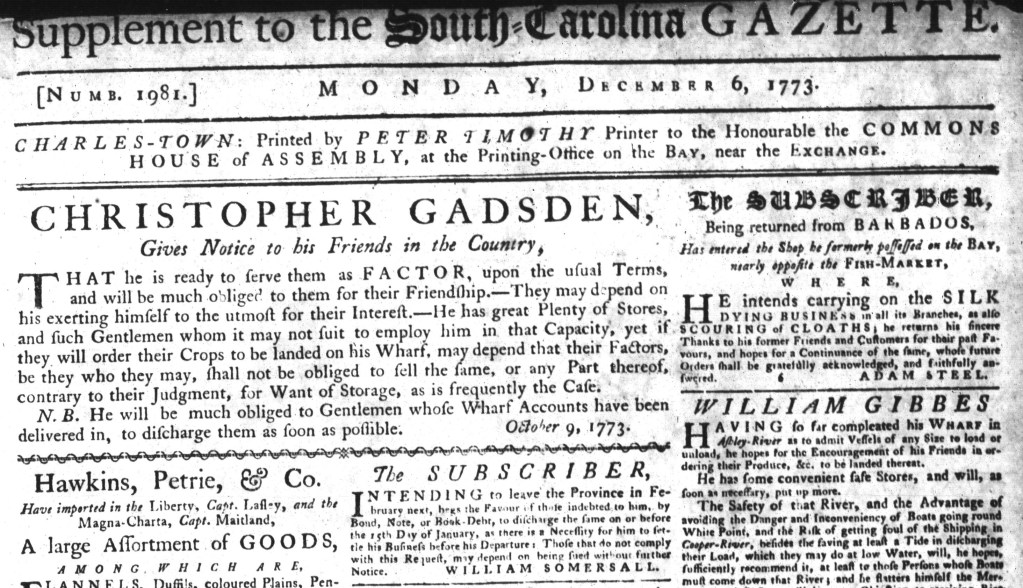

On and off for several months, Thomas Ash, a “WINDSOR CHAIR MAKER, At the Corner below St. Paul’s Church, In the Broad Way,” adorned his advertisement in Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer with a woodcut depicting the item that he made and sold. In contrast to Abel Buell’s advertisement featuring an image of a gun in the Connecticut Journal, Ash’s woodcut was not the only woodcut commissioned by an advertiser to appear in the March 3, 1774, edition of Rivington’s newspaper. Elsewhere in that issue, Nesbitt Deane once again ran an advertisement featuring a tricorne hat with his name on a banner unfurled beneath it. George Webster, “GROCER, AT THE SIGN OF THE Three Sugar Loaves & Scales,” included an image of three sugar loaves, two shorter ones flanking a taller one, enclosed within a simple border.

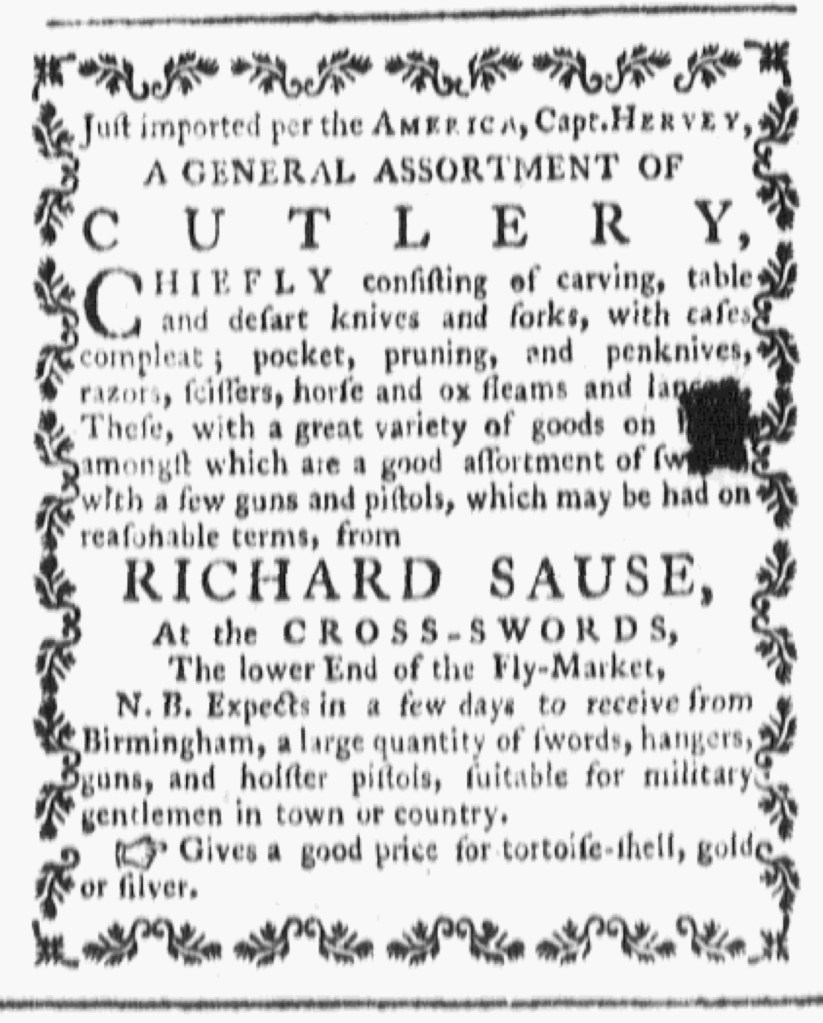

Those were not the only visual flourishes intended to draw attention to some of the advertisements in Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer. Decorative borders became a trademark of that newspaper. In the March 3 edition, five advertisements had such borders, including those placed by Richard Sause for merchandise at his “Hardware, Jewellery and Cutlery Store, John Siemon, a furrier, for muffs and tippets, John Simnet for cleaning and repairing watches, and S. Sp. Skinner for rum distilled in New York. Except for Simnet, all those advertisers had experience running other notices with decorative borders, as the links indicate. Simnet previously placed an identical advertisement, including the border. Sause and Siemon also sometimes ran advertisements with woodcuts tied to their businesses. Indeed, Siemon did so in the New-York Journal published the same day, choosing one method of adding visual interest in one newspaper and another method in the other. Webster was the fifth advertiser to use a border of decorative type, taking advantage of both methods in a single newspaper notice.

All the woodcuts and borders in Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer made its pages more vibrant than those in the Connecticut Journal. Advertisements with woodcuts and borders still stood out from others since most did not have either of those features, yet they collectively contributed to a cohesive look that distinguished newspapers published in busy ports from those printed in smaller towns.