What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

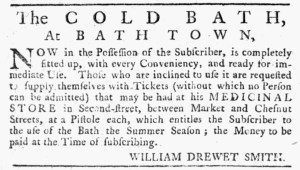

“The COLD BATH, At BATH TOWN.”

William Drewet Smith, a “Chemist and Druggist,” diversified his business interests in the spring of 1775. He operated a shop “At HIPPOCRATES’s HEAD” on Second Street Philadelphia, selling a “general Assortment of Druggs and patent medicines, surgeons instruments, [and] shop furniture.” In an advertisement in the March 25 edition of the Pennsylvania Ledger, he promoted one of those patent medicines, “Baron SCHOMBERG’s Grand Prophylactic LIMIMENT” to prevent venereal diseases and treat the symptoms of those who did not practice prevention soon enough. In that same issue, he inserted a second advertisement, that one hawking “Baron Van Haake’s royal letters pattent composition, for manuring land” to farmers and gardeners.

A week later, Smith ran yet another notice to announce that he was now the proprietor of the “COLD BATH, At BATH TOWN.” The facility, he reported, “is completely fitted up, with every Conveniency, and ready for immediate Use.” Those seeking entry needed to buy tickets (“without which no Person can be admitted”). The apothecary sold them for “a Pistole each” at his “MEDICINAL STORE.” Those who intended to travel to Bath, about sixty-five miles north of Philadelphia, could obtain their tickets before making the trip. Rather than a single admission, each ticket entitled the bearer “to the use of the Bath [throughout] the Summer Season,” but they had to pay the entire balance “at the Time of subscribing.” Smith did not allow guests to avail themselves of the amenities at his spa on credit.

Advertising in both the Pennsylvania Evening Post and the Pennsylvania Ledger, Smith joined the ranks of eighteenth-century entrepreneurs who marketed health tourism in America. The apothecary probably figured that it made sense to branch out in that direction. When clients visited his shop in Philadelphia, especially clients of means who had the leisure to travel, he could recommend the rejuvenating waters at the “COLD BATH” and the benefits of being away from the bustling urban port to supplement the medicines that he supplied. He likely believed that his reputation and experience as a “Chemist and Druggist” made him a trustworthy provider of other health services in the eyes of the public.