What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“OFFICE OF INTELLIGENCE.”

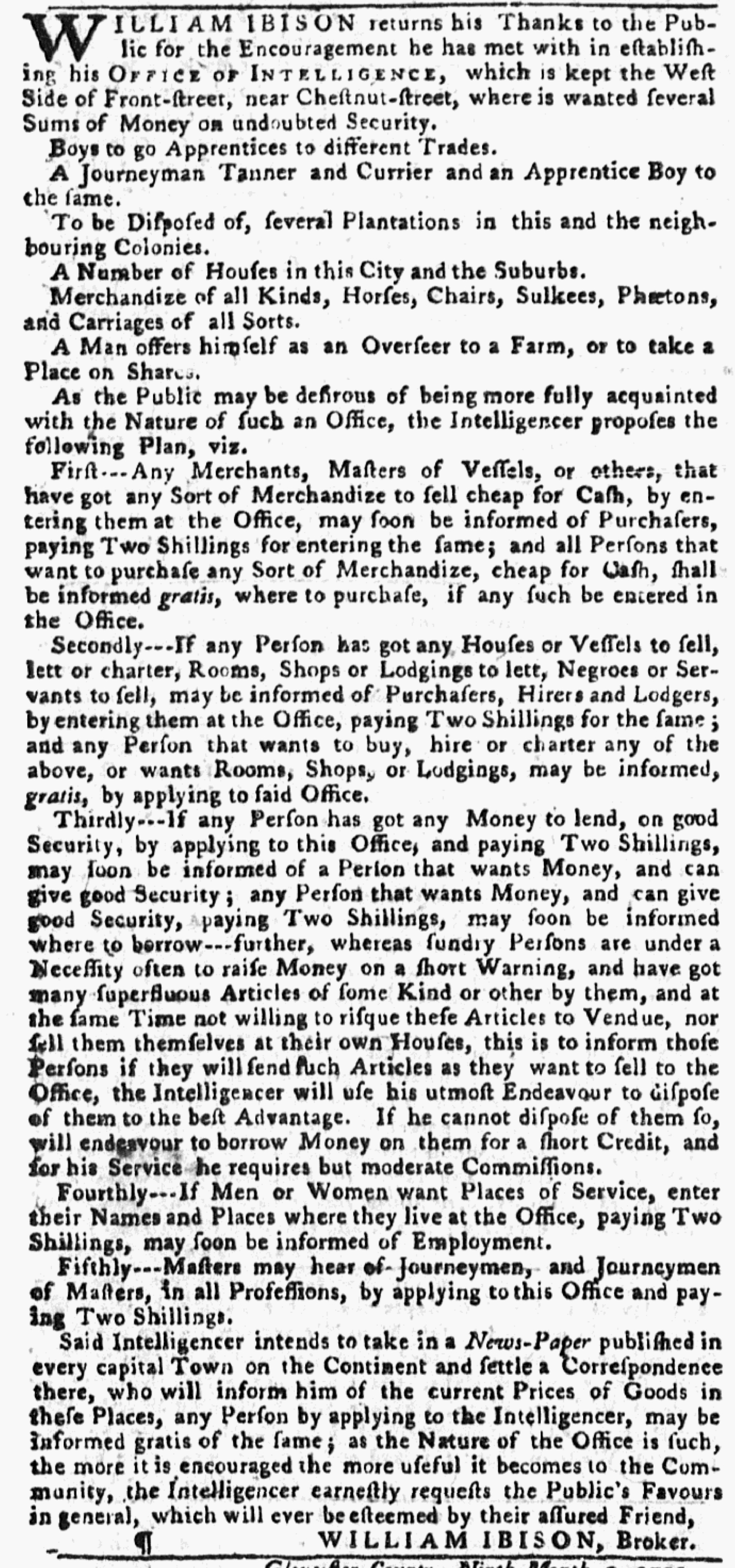

William Ibison offered his services as a broker to prospective clients who saw his advertisement in the September 12, 1771, edition of the Pennsylvania Gazette. He informed them that he established an “OFFICE OF INTELLIGENCE” on Front Street in Philadelphia. At that time, he could provide information about “Boys to go Apprentices to different Trades,” “A Number of Houses” for sale “in this City and the Suburbs,” and “Merchandize of all Kinds.”

Realizing that some readers might not have been familiar with the work of a broker or, as Ibison called himself, an “Intelligencer,” he offered an overview of his services. For a small fee, he collected information about goods for sale from “Merchants, Masters of Vessels, or others,” and then introduced them to prospective buyers. He also facilitated selling houses and ships, renting lodgings and shops, and selling indentured servants and enslaved laborers. In addition, Ibison oversaw loans and investments, placed men and women seeking work into jobs, and introduced masters and journeymen “in all Professions.” For each of those services, he charged “moderate Commissions” or small fees.

Ibison presented his “OFFICE OF INTELLIGENCE” as the hub of an information network. Some of that information he collected directly from clients, but he also relied on newspapers. The broker announced his plan “to take in a News-Paper published in every capital Town on the Continent and settle a Correspondence there.” Doing so would allow him to keep track of “current Prices of Goods in these Places” in order to pass along the intelligence to his clients. Unlike his other services, he offered that information “gratis.” He likely hoped that colonists who called on him for that information would be more likely to share information of their own or hire him for other ventures once they discovered how useful it could be to work with a broker who made it his business to collect, collate, and assess information from so many different sources.

The “Intelligencer” declared that “the Nature of the Office is such, the more it is encouraged the more useful it becomes to the Community.” His services, he asserted, benefited more than just his clients. That being the case, he “earnestly requests the Public’s Favours in general.” Only in combining a growing clientele with correspondents and newspapers from other cities could his “OFFICE OF INTELLIGENCE” achieve its full potential in assisting others in acquiring whatever information they needed to successfully pursue their own endeavors.