What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

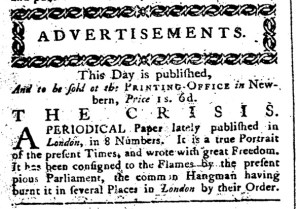

“THE CRISIS. A PERIODICAL Paper lately published in London, in 8 Numbers.”

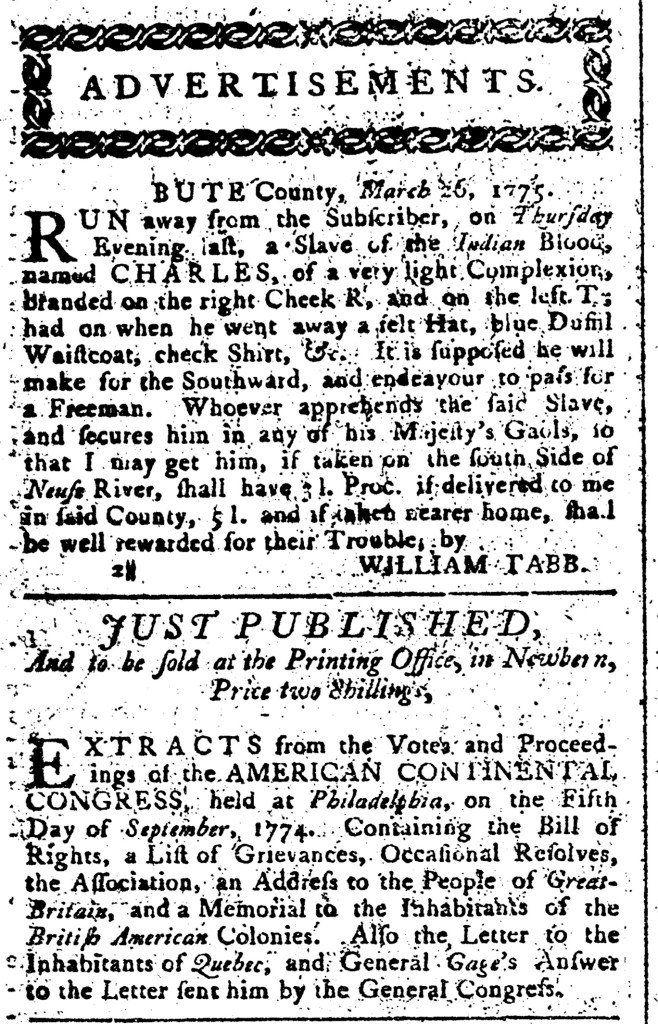

Along with continued coverage of the Battle of Bunker Hill, the July 14, 1775, edition of the North-Carolina Gazettecarried an advertisement for The Crisis, a “PERIODICAL Paper lately published in London, in 8 Numbers.” According to Neil L. York, The Crisis, published between January 1775 and October 1776, “was the longest-running weekly pamphlet series printed in the British Atlantic World during those years.” (That London publication should not be confused with Thomas Paine’s “American Crisis,” a series of essays published in the United States between 1776 and 1783.) The Crisis eventually included ninety-two editions, but James Davis, printer of the North-Carolina Gazette, had access to only the first eight. According to his advertisement, he collected them together into a single volume.

Davis used the pamphlet’s colorful history in marketing it to readers in North Carolina. “It is a true Portrait of the present Times,” he declared, “and wrote with great Freedom. It has been consigned to the Flames by the present pious Parliament, the common Hangman having burnt it in several Places in London by their Order.” York provides this overview: “The Crisis was condemned informally by leaders in the British government, and then formally in court, as a dangerous example of seditious libel [due to the depictions of George III]. Copies of it were publicly burned, and yet publication continued uninterrupted.” American Patriots had their supporters among the British public, including authors and printers who “played on shared beliefs and shared fears: beliefs in the existence of fundamental rights … and the fear that loss of those rights in Britain’s American colonies could lead to their loss in Britain itself.” York posits that the “men behind The Crisis were determined to interest the British public in American affairs and were no doubt pleased when various issues were reprinted in the colonies.” Indeed, newspapers reprinted some of the essays in their entirety. Printers also recognized opportunities to generate revenue while disseminating The Crisis to colonizers. Advertisements for individual numbers of the pamphlet peppered the pages of American newspapers in the spring and summer of 1775 as printers in several colonies distributed new issues as they came to hand. The day before Davis ran his advertisement in the North-Carolina Gazette, John Anderson announced in a notice in the New-York Journal that “on Monday will be published No. 9 of the CRISIS.” Instead of printing one issue at a time, Davis packaged the first eight issues together for readers, hoping that providing such convenient access would entice them to buy the volume.

**********

This entry marks the final appearance of the North-Carolina Gazette in the Adverts 250 Project. Few issues of that newspaper survive. Only seven, all of them from 1775, have been digitized for greater access via databases of early American newspapers. I have selected advertisements from the North-Carolina Gazette as often as possible to present a more complete representation of newspapers from throughout the colonies.