What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

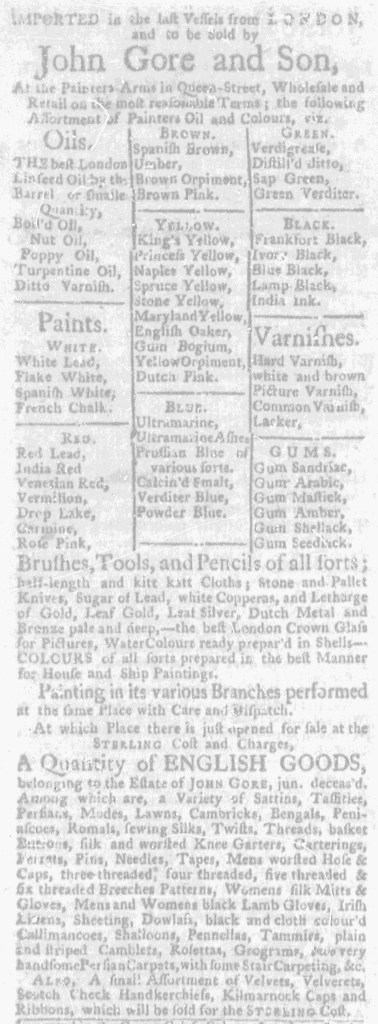

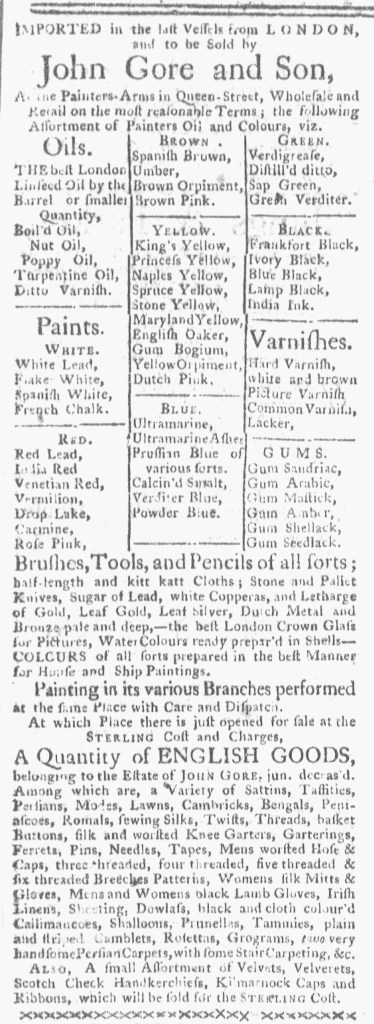

“Oils… Paints… Varnishes… GUMS.”

When it appeared in the Supplement to the Boston-Gazette on May 11, 1772, John Gore and Son’s advertisement for paint and supplies may have looked familiar to readers who regularly perused that newspaper. After all, it ran two weeks earlier in the April 27 edition. By the time the notice appeared in the Boston-Gazette a second time, it had also appeared in the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter twice, first on April 23 and then on May 7. The format made it memorable, an extensive list of oils, paints, varnishes, and gums arranged as a table. That table had sections for various shades of whites, reds, browns, yellows, blues, greens, and blacks, suggesting the many choices available to customers. No other advertisement in any of the newspapers published in Boston at the time incorporated that distinctive design.

It was not uncommon for advertisers to place notices in multiple newspapers in order to reach more consumers and increase their share of the market. When they did so, they usually submitted copy to the printing offices and then compositors made decisions about the design of each advertisement when they set the type. That meant that advertisements with identical copy had variations in line breaks, font sizes, italics, and capitalization from newspaper to newspaper, depending on the decisions made by compositors. In some instances, advertisers made requests or included instructions. For example, some merchants and shopkeepers preferred for their merchandise to appear in two columns with only one item on each line rather than in a dense block of text. In such cases, compositors still introduced variations in graphic design, even when working with identical copy.

That did not happen with Gore and Son’s advertisement. Instead, the same advertisement ran in both the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter and the Boston-Gazette. Workers in the two offices transferred type already set back and forth multiple times. When the time the advertisement appeared in the Supplement to the Boston-Gazette, three transfers had taken place, first from Richard Draper’s printing office to the Benjamin Edes and John Gill’s printing office, then a return to Draper’s office, and once again to Edes and Gill’s office. Early American printers frequently reprinted content from one newspaper to another. That was standard practice for disseminating news, but it did not involve the coordination and cooperation required for sharing type. Gore and Son’s advertisement suggests even greater collaboration among printers in Boston, a relationship that merits further investigation to understand how they ran their businesses.