What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“This Pamphlet run thro’ Ten Editions in London in less than twelve Months.”

American printers and booksellers marketed and sold a variety of political pamphlets and treatises during the imperial crisis that led to thirteen colonies declaring independence from Great Britain. In addition to hawking items printed in London and imported to the colonies, some of those printers and booksellers also published American editions, as was the case with The Judgment of Whole Kingdoms and Nations, Concerning the Rights, Privileges and Properties of the People. Three American editions appeared in 1773 and 1774, one in Philadelphia, one in Boston, and one in Newport, Rhode Island.

Several rare book dealers, including Bauman Rare Books, offer overviews of the publication history, contents, and significance of The Judgment of Whole Kingdoms and Nations. Originally published as Vox Populi, Vox Dei in London in 1709, the pamphlet “examines principles of limited monarchy and the right of resistance to tyranny,” drawing on “historical precedents and reiterat[ing] opposition to absolute monarchy during the time of England’s Glorious Revolution.” Colonial printers and booksellers both answered the demand for this sort of political philosophy and helped to stoke opposition to king and Parliament by publishing and disseminating this pamphlet and other tracts and treatises. The Judgment of Whole Kingdoms and Nations “contains the seed of what would become the American Bill of Rights – reprinting the English Bill of Rights – and was read by many of the Founding Fathers, including John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, who owned the Philadelphia 1773 edition.”

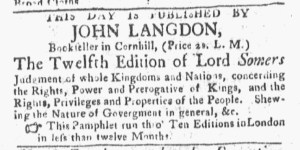

Adams may have acquired his copy after reading the advertisement that John Langdon placed in the February 7, 1774, edition of the Boston-Gazette, a newspaper that took an especially vocal stance in support of the Sons of Liberty and the rights of Americans. Langdon, a bookseller, published the book, engaging the services of Isaiah Thomas as printer. To incite demand, Langdon informed prospective customers that “This Pamphlet run thro’ Ten Editions in London in less than twelve Months.” How could anyone interested in politics in the colonies miss out on what was such a popular and influential work in the capital of the empire? Readers of the Boston-Gazette had to decide for themselves how much to trust Langdon’s assertion about the rapid sales of the pamphlet in London.

That report, however, may have contributed to colonizers overestimating how much the general public on the other side of the Atlantic supported them in their disputes with George III and Parliament. In Misinformation Nation: Foreign News and the Politics of Truth in Revolutionary America, Jordan E. Taylor argues that American newspapers selectively published reports from London, creating narratives of recent events that matched the ideologies of the printers. Langdon’s note at the end of his advertisement for a political pamphlet used to support the American cause may have buttressed the narrative that Benjamin Edes and John Gill advanced in the news items and editorials they published elsewhere in the Boston-Gazette. Declaring that The Judgment of Whole Kingdoms and Nations sold so rapidly in London suggested widespread support for the principles it contained as well as applying them to the American colonies.