What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“The above pamphlet … is quoted in a respectful manner by the Earl of Chatham.”

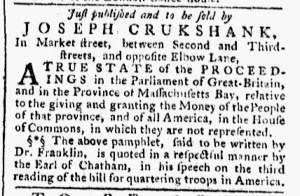

Two weeks after the First Continental Congress commenced its meetings in Philadelphia, Joseph Crukshank took to the pages of Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Gazette to advertise that he had “Just published … A TRUE STATE of the PROCEEDINGS in the Parliament of Great-Britain, and in the Province of Massachusetts Bay, relative to the giving and granting the Money of the People of that province, and of all America, in the House of Commons, in which they are not represented.” As was often the case, the extensive title simultaneously provided an overview of the pamphlet’s contents and served as advertising copy.

Yet that was not the only appeal made in this advertisement. Crukshank, the printer of this American edition of a work originally published in London, sought to entice buyers with additional information. “The above pamphlet, said to be written by Dr. Franklin,” he informed readers, “is quoted in a respectful manner by the Earl of Chatham, in his speech on the third reading of the bill for quartering troops in America.” Colonizers had long celebrated William Pitt the Elder for his advocacy on their behalf, doing so once again when he considered the wisdom of the Quartering Act, one of the Coercive Acts that Parliament passed in the wake of the Boston Tea Party. Historians have determined that Arthur Lee compiled the pamphlet from material furnished by Benjamin Franklin.

The title of the pamphlet, including its reference to the colonies lacking direct representation in Parliament, buttressed the arguments presented in letters and editorials that ran elsewhere in the September 19, 1774, edition of Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet. On its own, the advertisement operated as a miniature editorial among the other content of the newspaper. Scholars debate the extent that political pamphlets shaped public opinion, some arguing that newspapers reached many more people. Compared to pamphlets, newspapers were inexpensive, plus they circulated widely. Yet advertisements for political pamphlets did important work, even if few readers opted to purchase or read those pamphlets. The advertisements contributed to an impression of the discourse taking place, signaling to readers what others believed about current events and why they should prefer one position over another. Most readers of Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet never purchased Crukshank’s American edition of a political pamphlet originally published in London, yet the advertisement relayed information about the position taken by a popular politician and made an argument about the colonies’ lack of representation in Parliament. The advertisement became part of the news environment.