What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

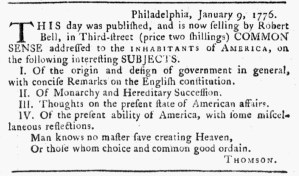

“THIS day was published … COMMON SENSE addressed to the INHABITANTS of AMERICA.”

On January 9, 1776, the first advertisement for Thomas Paine’s Common Sense appeared in an American newspaper. The notice did not include Paine’s name. Instead, it stated that Robert Bell, the prominent printer and bookseller, “published, and is now selling … COMMON SENSE addressed to the INHABITANTS of AMERICA, on the following subjects.” The advertisement then listed the headings for the several sections in the first edition: “I. Of the origin and design of government in general, with concise Remarks on the English constitution. II. Of Monarchy and Hereditary Succession. III. Thoughts on the present state of American affairs. IV. Of the present ability of America, with some miscellaneous reflections.”

Over the next several months, printers in many towns would publish and advertise local editions of Common Sense, making it the most widely disseminated political pamphlet during the era of the American Revolution (though, as Trish Loughran convincingly demonstrates, the number of copies has been wildly exaggerated).[1] Historians also consider Common Sense the most persuasive pamphlet that advocated for the American cause. Even though hostilities commenced at Lexington and Concord in April 1775, many Americans still hoped that the king would intervene to address their grievances. The plain language of Common Sense (along with unflattering depictions of monarchy) played a significant role in convincing many colonizers to support independence over a redress of grievances. Paine made a strong case for “the present ability of America” to establish a new government and trading relationships beyond the British Empire.

There seems to be some confusion about the publication date for Common Sense. Some sources claim that it was published on January 10, 1776. I suspect that is because advertisements for the pamphlet first appeared in the January 10 editions of the Pennsylvania Gazette, the newspaper Benjamin Franklin formerly operated, and the Pennsylvania Journal, published by Patriot printers William Bradford and Thomas Bradford. Those advertisements featured almost identical copy (but different choices for the format made by the compositors), including the phrase “THIS DAY IS PUBLISHED” in the Pennsylvania Gazette and “This Day was Published” in the Pennsylvania Journal. I have previously examined other instances of similar phrases, demonstrating that they did not literally refer to the publication date but instead meant that a book or pamphlet was now available for purchase. When the advertisement ran in the Pennsylvania Ledger on January 13 and in the Wochentliche Pennsylvanische Staatsbote on January 16, both versions stated, “This Day was Published.” Eighteenth-century readers knew how to interpret the phrase. I wonder if some scholars consulted the more famous and the more venerable Pennsylvania Gazette (founded 1728) and Pennsylvania Journal (founded 1742), saw a phrase that suggested the date of the newspaper was indeed the publication date for Common Sense, and overlooked a newspaper that had been in production for a little less than a year when it carried its first advertisement for Common Sense. (Benjamin Towne distributed the first issue of the Pennsylvania Evening Post on January 24, 1775.) Bell may have been selling copies of Common Sense before January 9. The advertisement in the Pennsylvania Evening Post does not definitively demonstrate that the pamphlet was published on January 9, but it does show when marketing for the pamphlet began and that Bell published it no later than January 9, 1776.

**********

[1] Trish Loughran, “Disseminating Common Sense: Thomas Paine and the Problem of the Early National Bestseller,” American Literature 78., no. 1 (March 2006), 1-28.