What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“He has had the Opportunity of seeing the present Taste in London, as it is now executed.”

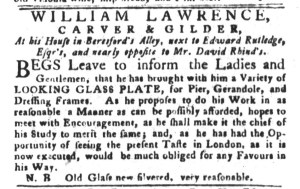

William Lawrence, a “CARVER & GILDER,” offered his services to “the Ladies and Gentlemen” of Charleston in an advertisement in the August 30, 1774, edition of the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal. He had a “Variety of LOOKING GLASS PLATE” that he could fit to “Pier, Gerandole, and Dressing Frames.” Though those items may sound unfamiliar today, eighteenth-century consumers recognized each of those kinds of mirrors and understood their purposes. As the Oxford English Dictionary explains, a pier glass was a “large mirror, originally one fitted in the space between two windows, or over a chimney piece.” The frame often matched the design of the windows. These large mirrors reflected light to better illuminate rooms. That was also the purpose of girandoles fitted with mirrors. Those branched supports held candles, the mirrors multiplying the light. Finally, dressing glasses sat on dressing tables or were hung above them, allowing users to view themselves as they prepared their hair and jewelry.

Although practical, each of these items had the potential to be elegant, testifying to the good taste of the men and women who displayed them in their homes. Lawrence emphasized that aspect of the looking glasses he framed. He alluded to a recent trip to London, the cosmopolitan center of the British Empire, asserting that he “has had the Opportunity of seeing the present Taste in London, as it is now executed.” Consumers in Charleston, New York, Philadelphia, and other major urban ports closely followed London fashions, adopting them quickly to demonstrate their own gentility rather than risk appearing unsophisticated in comparison to the gentry on the other side of the Atlantic. During his journey, Lawrence apparently selected plates that he “brought with him” when he returned to Charleston, believing that this personal connection, rather than ordering them from afar, would enhance their value and his ability to market them. He intended that his firsthand observation of current London fashions and subsequent selection of materials gave him an advantage over other carvers and gilders in Charleston.