GUEST CURATOR: Nicholas Commesso

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

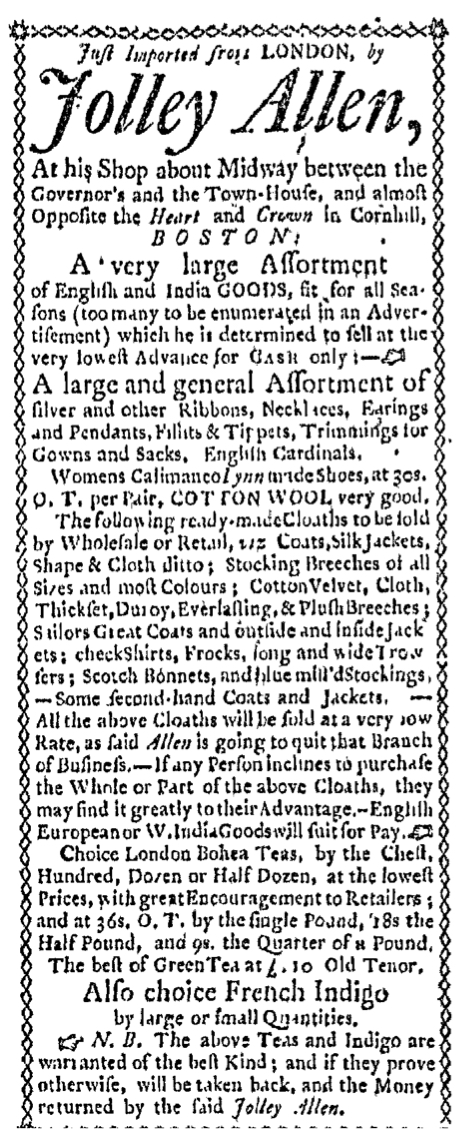

“Warranted of the best Kind; and if they prove otherwise, will be taken back, and the Money returned.”

Jolley Allen’s lengthy advertisement from the Boston Evening-Post features countless common products seen in numerous other advertisements, including tea, silks, textiles, and jewelry. In addition to a long list of merchandise, this one had something else included at the end. Many of the advertisements I have looked at claimed to be selling their assortment of goods the cheapest, and they promised the highest quality products around. However, Allen is the first one I have seen who actually backed it up. This advertisement concluded with a guarantee that if the “Teas and Indigo” were not of the “best Kind,” they “will be taken back, and the Money returned by the said Jolley Allen.”

Allen put his name and reputation on the line. He displayed his character in a way favorable to consumers. With the expansion of consumer culture in the colonies, it would have been easy for shopkeepers to make all sales final, yet with more shops opening, consumers could take their business elsewhere. Allen was committed to his name, his shop, and his goods, and made it a point for his shop to stand out from the rest. After further research, however, I also learned that Allen was a Loyalist entrepreneur; it’s interesting that he became a successful businessman regardless of his controversial political views.

**********

ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY: Carl Robert Keyes

Jolley Allen operated his business in an increasingly politicized colonial marketplace. His own politics, however, were not apparent in this particular advertisement. That he was a Loyalist, we learn from other sources from the period.

That’s not to say, however, that all newspaper advertisement published during the imperial crisis of the 1760s and 1770s lacked a political valence. As soon as the colonists learned of the Stamp Act, many advertisers made explicitly partisan appeals as part of their marketing messages, often promoting domestic manufactures or condemning the effects that Parliament’s actions would have on commerce. After the Stamp Act was repealed, some entrepreneurs inserted their own brief celebratory proclamations into their advertisements; even when they did not directly connect the Stamp Act to the merchandise they advertised, they assumed that their political views would influence potential customers to visit their shops.

As a Loyalist, Jolley Allen certainly did not condemn Parliament nor celebrate the demise of the Stamp Act in his advertisements. The advertisements he published in 1766 were devoid of politics, yet Boston was not so large that his political views would have been unfamiliar to friends, neighbors, and potential customers. Perhaps that played a role in inspiring some of the innovative aspects of his advertisements: he needed to overcome suspicions of his allegiances and used distinctive marketing to do so. Nick identified Allen’s reputation and stature as an honest trader as one means of promoting his shop “Opposite the Heart and Crown in Cornhill, BOSTON.” Although not the first colonial advertiser to offer some form of money-back guarantee, he did make an offer that was not a standard part of eighteenth-century advertising. In addition, his advertisements consistently featured distinctive graphic design elements, namely a decorative border, intended to draw more eyes than competitors’ advertisements that appeared elsewhere on the page. Allen also advertised extensively, placing the same advertisement in all four newspapers published in Boston in 1766, thus reaching the largest possible audience of potential customers despite the political leanings of any particular newspaper or its printer.