What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this month?

“American Magazine. ‘To be, or not to be.’”

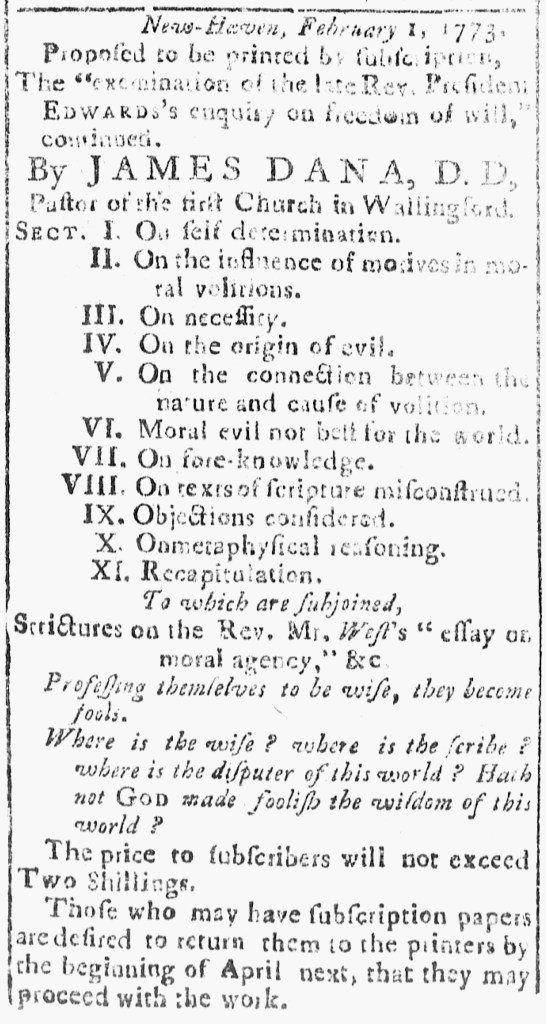

In the summer and fall of 1773, Isaiah Thomas advertised widely in his efforts to attract subscribers for the Royal American Magazine, a proposed publication that would become the only magazine published in the colonies at the time if the printer managed to generate enough interest to make it a viable venture. On October 25, he placed advertisements in the Boston-Gazette and the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Post-Boy with a secondary headline that proclaimed “To be, or not to be,” a familiar quotation from Shakespeare’s Hamlet, to indicate that the prospects of the publication remained uncertain. In both newspapers, Thomas requested that anyone who recruited subscribers return the subscription papers with the lists of names by the middle of November “as by that Time he shall be able to determine, whether the said Magazine will be Published or not.” The advertisement in the Boston-Gazette also included a nota bene in which Thomas confided that “by the Appearance of the Subscription papers, in his Possession, there is the greatest Probability of its going forward.” Thomas would indeed publish the first issue in January 1774, though the magazine lasted only sixteen months due to the disruptions of the imperial crisis and, eventually, the war that began with the skirmishes at Lexington and Concord in April 1775.

The Adverts 250 Project has traced the advertising campaign that promoted the Royal American Magazine in June, July, August, and September. An even greater number of advertisements appeared in colonial newspapers in October than in any previous month, a total of twenty advertisements in ten newspapers in eight towns in six colonies. Three of those advertisements ran in Thomas’s own Massachusetts Spy, while other newspapers carried the vast majority of them. Fourteen of the advertisements appeared in newspapers published beyond Boston. Thomas sought subscribers who read newspapers published in Salem, Massachusetts; Portsmouth, New-Hampshire; Newport, Rhode Island; New Haven and New London in Connecticut; and New York and Philadelphia. Previously, the Connecticut Courant, published in Hartford, and the Providence Gazette also carried the subscription proposals for the Royal American Magazine. Thomas knew the number of prospective subscribers in Boston alone would not justify an investment of the time and resources required to publish a magazine. He devised an advertising campaign that extended to all of the colonies in New England as well as New York and Pennsylvania.

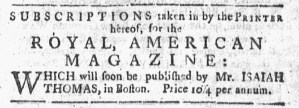

In October 1773, the subscription proposals appeared once again in the Connecticut Journal and the Pennsylvania Journal. The printer’s update addressed “To the Public” made additional appearances in the Boston-Gazette and the Massachusetts Spy. It also ran for the first time in the Essex Gazette, published in Salem, and had two more insertions during the month. Having published the subscription proposals in July and August, the Newport Mercury carried a unique advertisement, likely devised by Solomon Southwick, the printer and Thomas’s local agent for collecting the names of subscribers, rather than by Thomas himself. It announced, “SUBSCRIPTIONS taken in by the Printer hereof, FOR THE ROYAL AMERICAN MAGAZINE: WHICH will soon be published by Mr. ISAIAH THOMAS, in Boston. Price 10s4 per annum.”

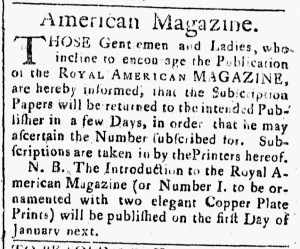

That advertisement expressed greater certainty about the prospects for the magazine than Thomas’s “To be, or not to be” notice that ran in Boston later in the month, as did another update that Thomas placed in newspapers in Connecticut, New Hampshire, and New York near the end of the month. That advertisement informed “Gentlemen and Ladies, who incline to encourage the Publication of the ROYAL AMERICAN MAGAZINE … that the Subscription Papers will be returned to the intended Publisher in a few Days, in order that he may ascertain the Number subscribed for.” Those who had not yet submitted their names to the local printing office had only a limited time to do so. As an enticement to those still contemplating whether they wished to subscribe, a nota bene promoted “two elegant Copper Plate Prints” that would accompany the first issue of the magazine. The nota bene also indicated a publication date, “the first Day of January next.” Along with the magazine, prospective subscribers did not have much time to qualify for these premiums. If they decided to subscribe at some time in the future, they would miss out on the gift given to those who supported the magazine even before the first issue went to press.

Thomas hoped to publish the Royal American Magazine, but first he needed to determine if a market existed to support it. His subscription proposals and other advertisements served a dual purpose: they incited demand for the magazine while also assessing interest and determining the total number of subscribers willing to pay for the publication. Some subscription proposals, no matter how widely they circulated, never resulted in publishing the proposed book, magazine, map, or other item. Over the course of several months, Thomas managed to identify and incite sufficient demand to publish the Royal American Magazine.

**********

Newspaper Advertisements for October 1773

Subscription Proposals

- October 8 – Connecticut Journal (second known appearance; fourth possible appearance)

- October 20 – Postscript to the Pennsylvania Journal (second appearance)

“To the PUBLIC” Update

- October 4 – Boston-Gazette (third appearance)

- October 7 – Massachusetts Spy (third appearance)

- October 12 – Essex Gazette (first appearance)

- October 14 – Massachusetts Spy (fourth appearance)

- October 19 – Essex Gazette (second appearance)

- October 21 – Massachusetts Spy (fifth appearance)

- October 26 – Essex Gazette (third appearance)

“SUBSCRIPTIONS” Notice

- October 4 – Newport Mercury (first appearance)

- October 11 – Newport Mercury (second appearance)

- October 18 – Newport Mercury (third appearance)

- October 25 – Newport Mercury (fourth appearance)

“Subscription Papers will be returned” Update

- October 22 – Connecticut Journal (first appearance)

- October 22 – New-Hampshire Gazette (first appearance)

- October 22 – New-London Gazette (first appearance)

- October 28 – New-York Journal (first appearance)

- October 29 – Connecticut Journal (second appearance)

“To be, or not to be” Update

- October 25 – Boston-Gazette (first appearance)

- October 25 – Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Post-Boy (first appearance)