What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

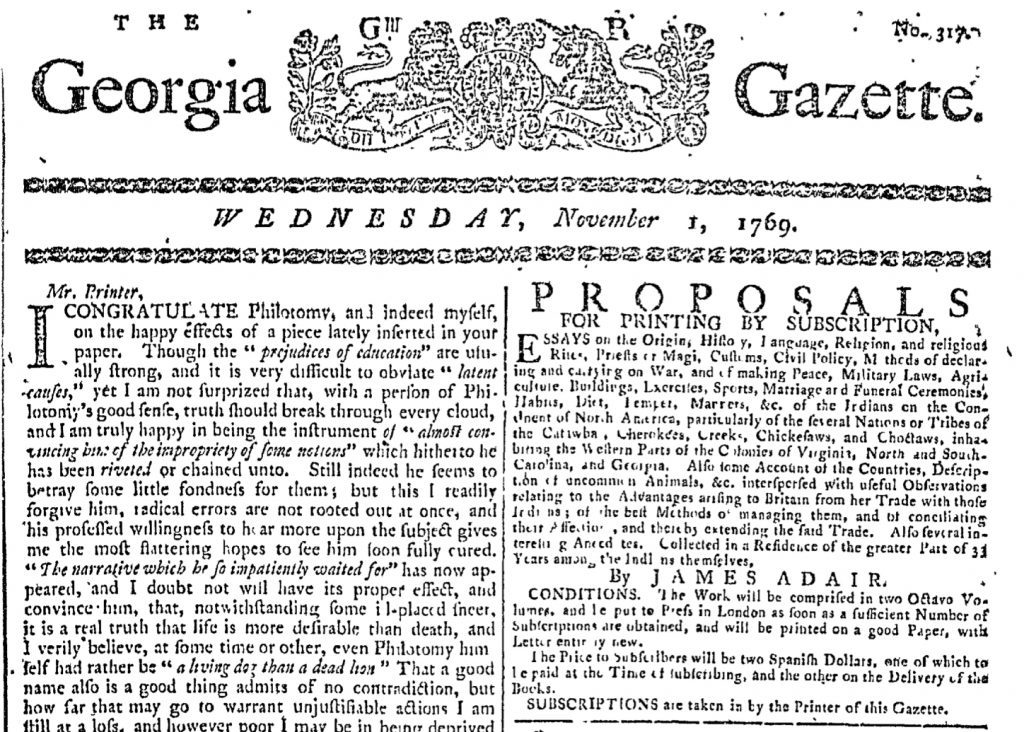

“PROPOSALS FOR PRINTING BY SUBSCRIPTION.”

A subscription notice for “ESSAYS on … the Indians of the Continent of North America, especially the several Nations or Tribes of the Catawbas, Cherokees, Creeks, Chicksaws, and Choctaws, inhabiting the Western Parts of the Colonies of Virginia, North and South Carolina, and Georgia” once again ran in the January 17, 1770, edition of the Georgia Gazette. The advertisement made its first appearance of the new year, not having been among the various notices disseminated in that newspaper since November 22, 1769. Previously, it ran on the front page of the November 1 edition.

These “PROPOSALS FOR PRINTING BY SUBSCRIPTION” appeared sporadically, separated by three weeks and then by eight. That deviated from standard practices for advertisements promoting consumer goods and services in the Georgia Gazette. They usually ran in consecutive issues for a limited time, often three or four weeks. James Johnston, the printer of the Georgia Gazette, devised a different publication schedule for this particular advertisement.

Johnston served as a local agent for either James Adair, the author of the proposed book, or an unnamed printer in London or a combination of the two. Local agents were responsible for distributing subscription notices, collecting the names of subscribers, and transmitting the list to the author or printer. Local agents also collected payment and delivered books to the subscribers.

Given his familiarity with local markets, Johnston likely determined that a series of advertisements concentrated in a short period would not incite as much interest as introducing potential subscribers to the proposed work on multiple occasions over several months. Considerations of space may have also influenced his decisions about when he published the subscription notice. It received a privileged place the first time it ran in the Georgia Gazette, but for each of the subsequent iterations it appeared as the last item at the bottom of a column. That suggests the compositor held the advertisement in reserve, inserting it only once news and other advertisements were allocated space in an issue. As a local agent, Johnston had been entrusted with some latitude in making decisions about distributing subscription notices for a book that would be published on the other side of the Atlantic. Both his understanding of local markets and his own business interests likely had an impact on his methods of marketing the proposed book.